Pueblo Gardens, 1948

Del E. Webb and architects A. Quincy Jones & Paul R. Williams vision for the future. By Elissa Schirmer Erly

Del E. Webb and architects A. Quincy Jones & Paul R. Williams vision for the future. By Elissa Schirmer Erly

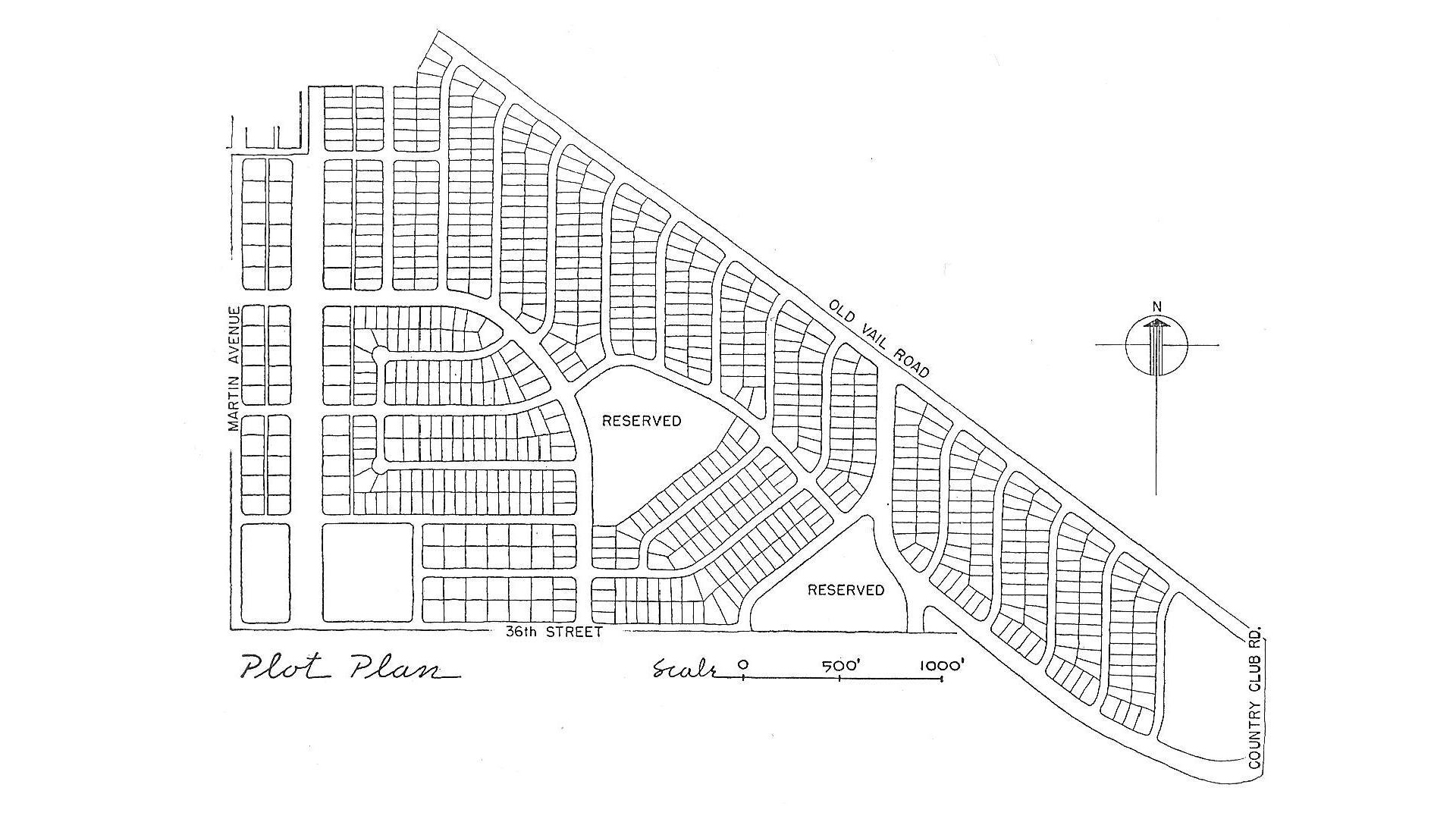

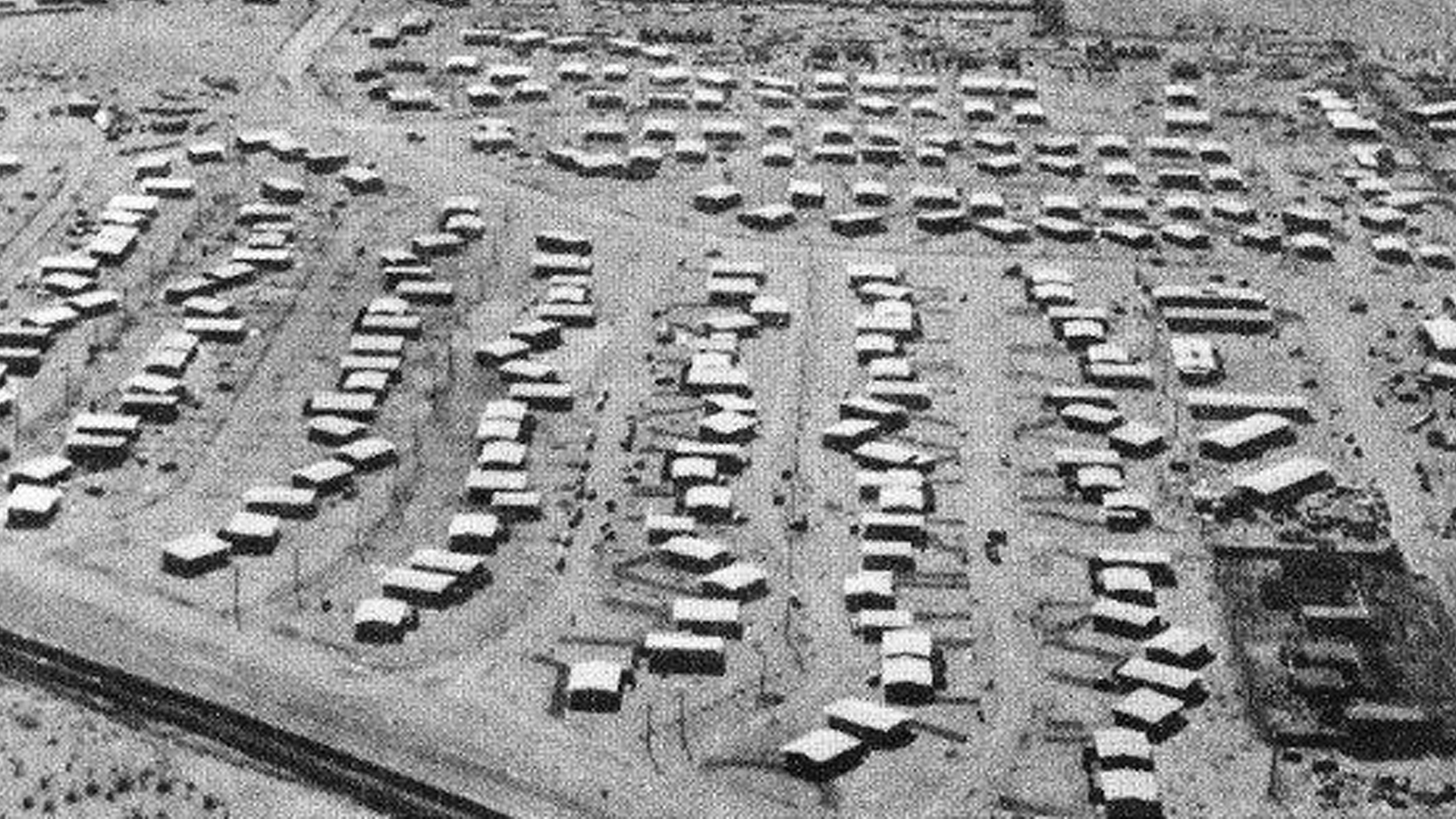

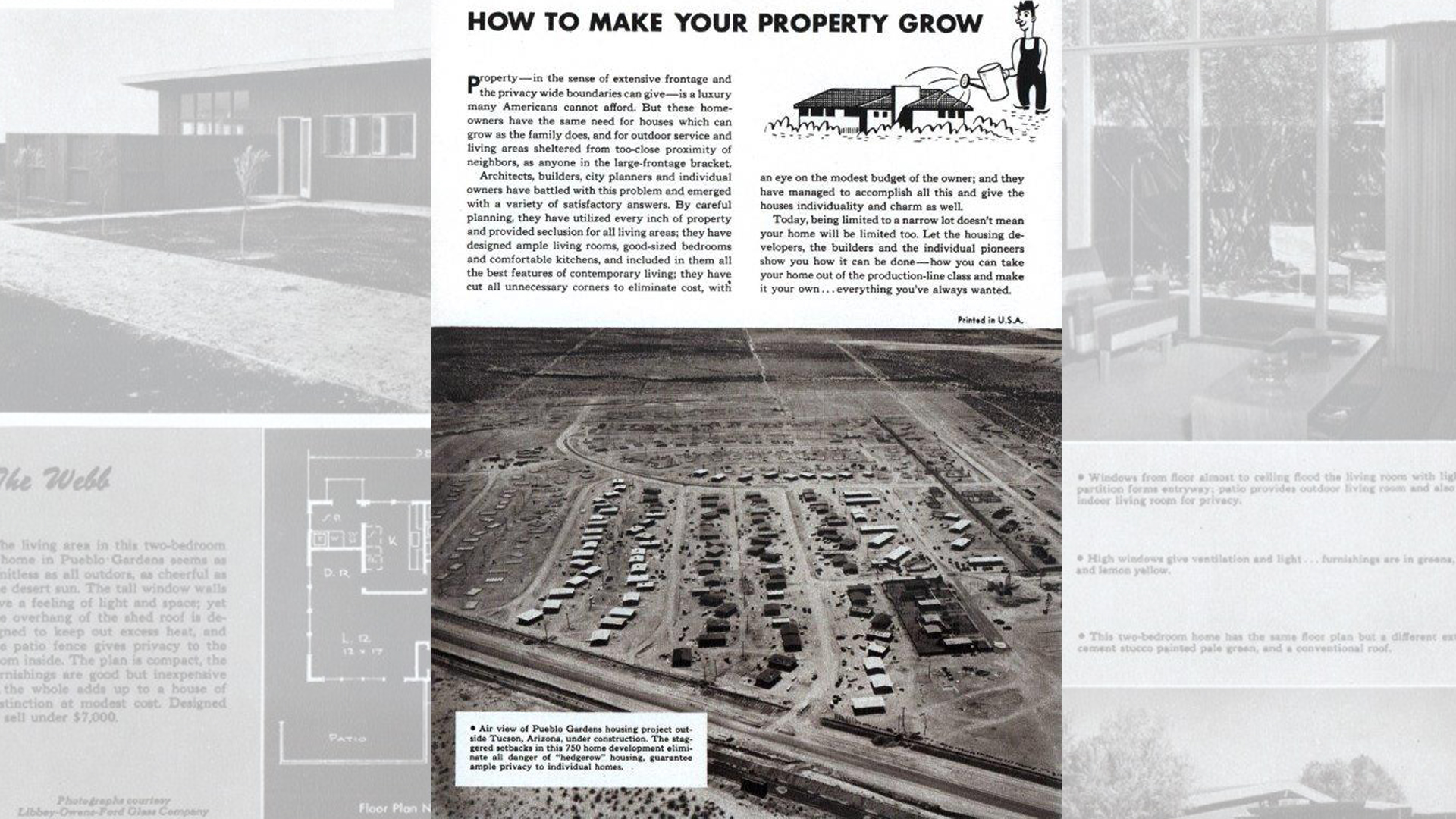

In 1948, Building contractor, and Yankees team owner, Del E. Webb (1899-1974) broke ground on the first large-scale housing development in Tucson, Arizona (Stewart E4). Pueblo Gardens, as the subdivision was named, was to include 3,000 homes, making it the largest housing development between Dallas and Los Angeles (Graham 12A). Tucson real estate pioneer Roy P. Drachman (1906-2002) sold the land for the project to Webb and managed the sales of the homes (Walker 1E).

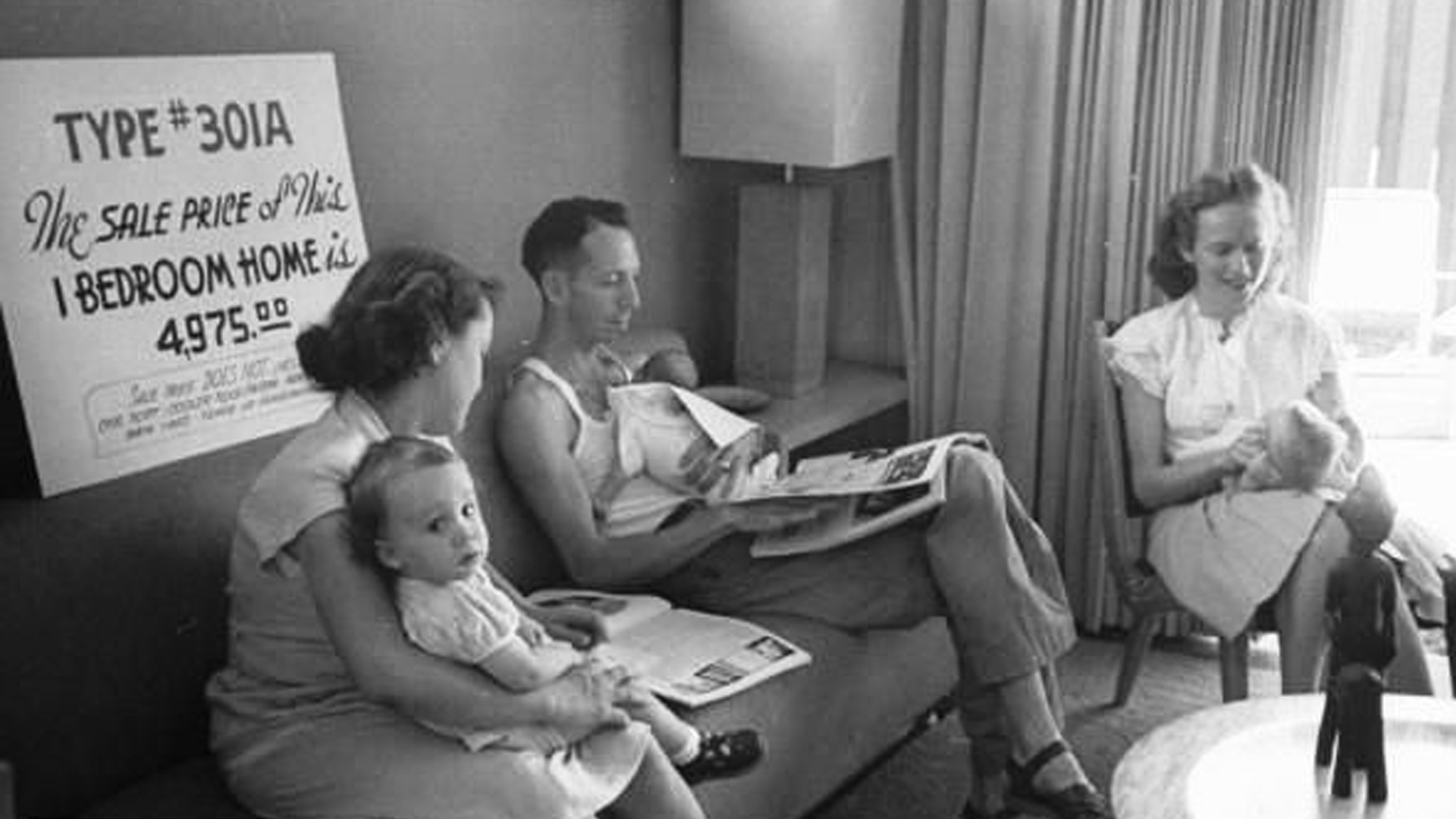

There were six models initially offered, ranging from $5,000. for a one bedroom home to a three bedroom home for $8,000 (“Tucson Developer”). The modestly priced houses were attractive to Air Force families and WWII veterans, such as Joanne and Perry Baker, the first family to purchase a home in the neighborhood (Graham, “Hope Blooms” 1A).

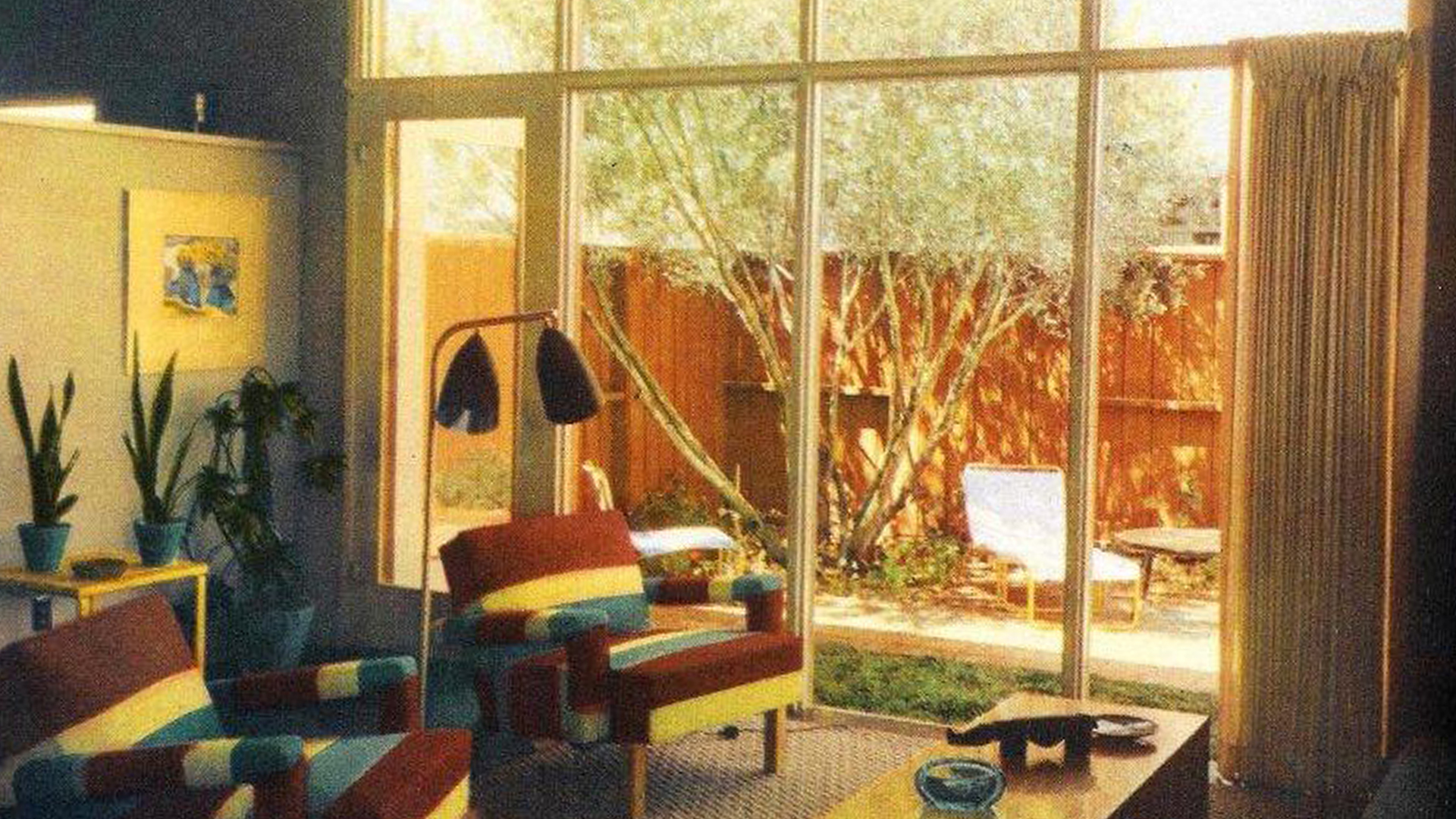

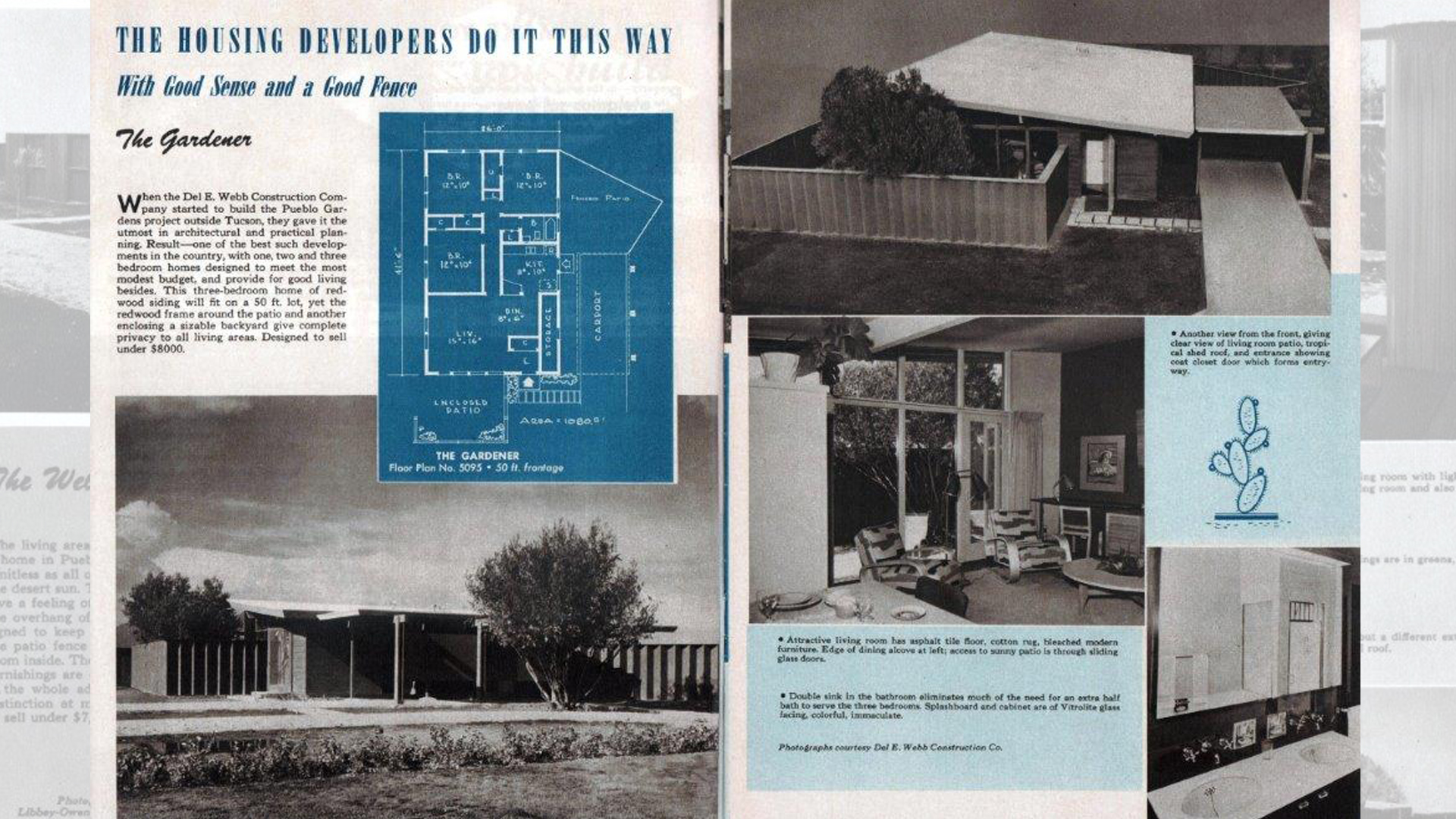

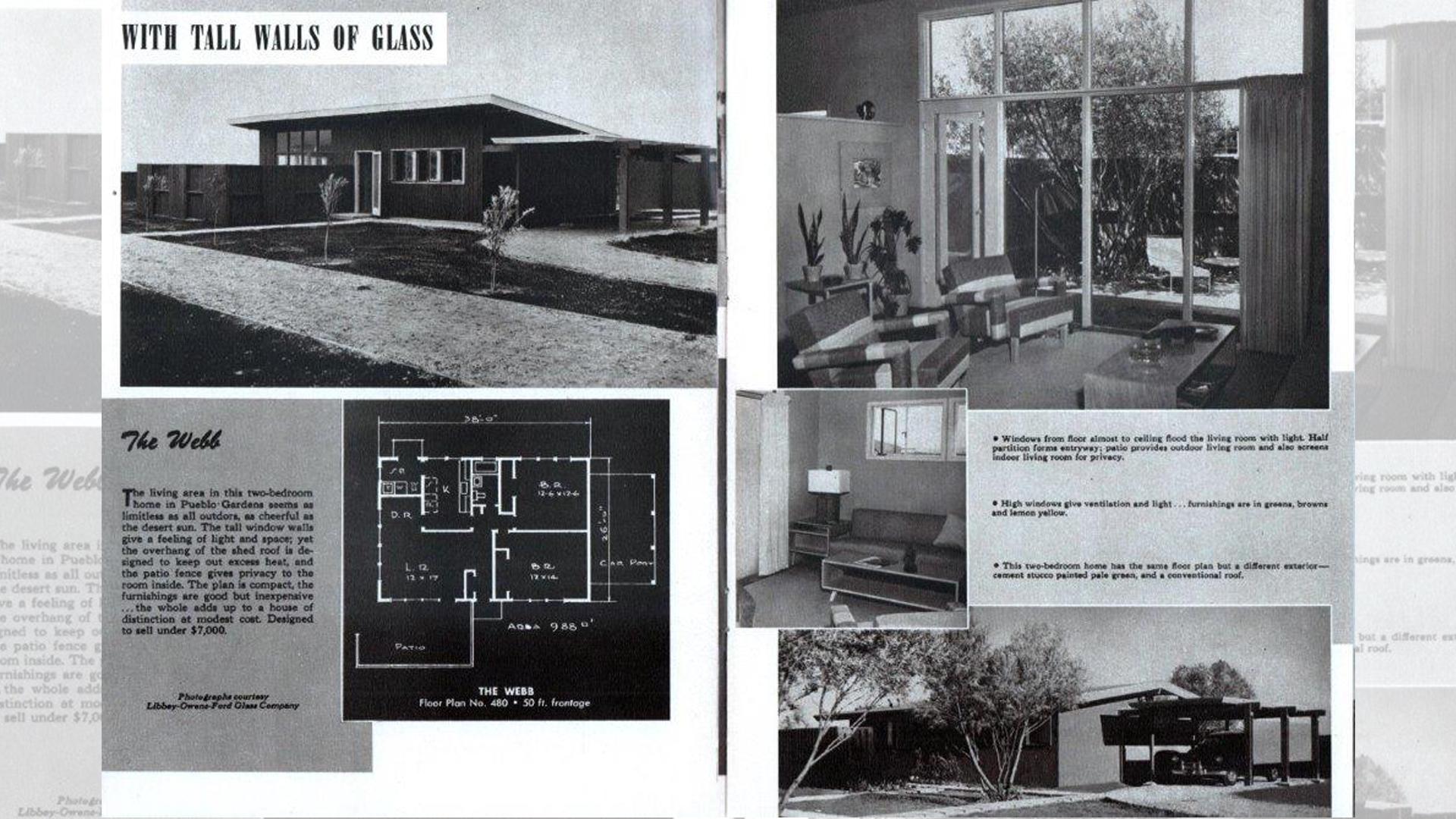

The Pueblo Garden subdivision was the first in Tucson to feature wood-frame construction rather than masonry (Stewart E4). Architects Paul R. Williams and A. Quincy Jones Jr. included other architectural innovations, such as window walls, wide overhangs and sloping ceilings to visually enlarge the rooms (“Products for Better Living” 153). Outdoor patio walls continued into the house, becoming living room walls to blur the distinction between indoor and outdoor spaces (“Tucson Developer”).

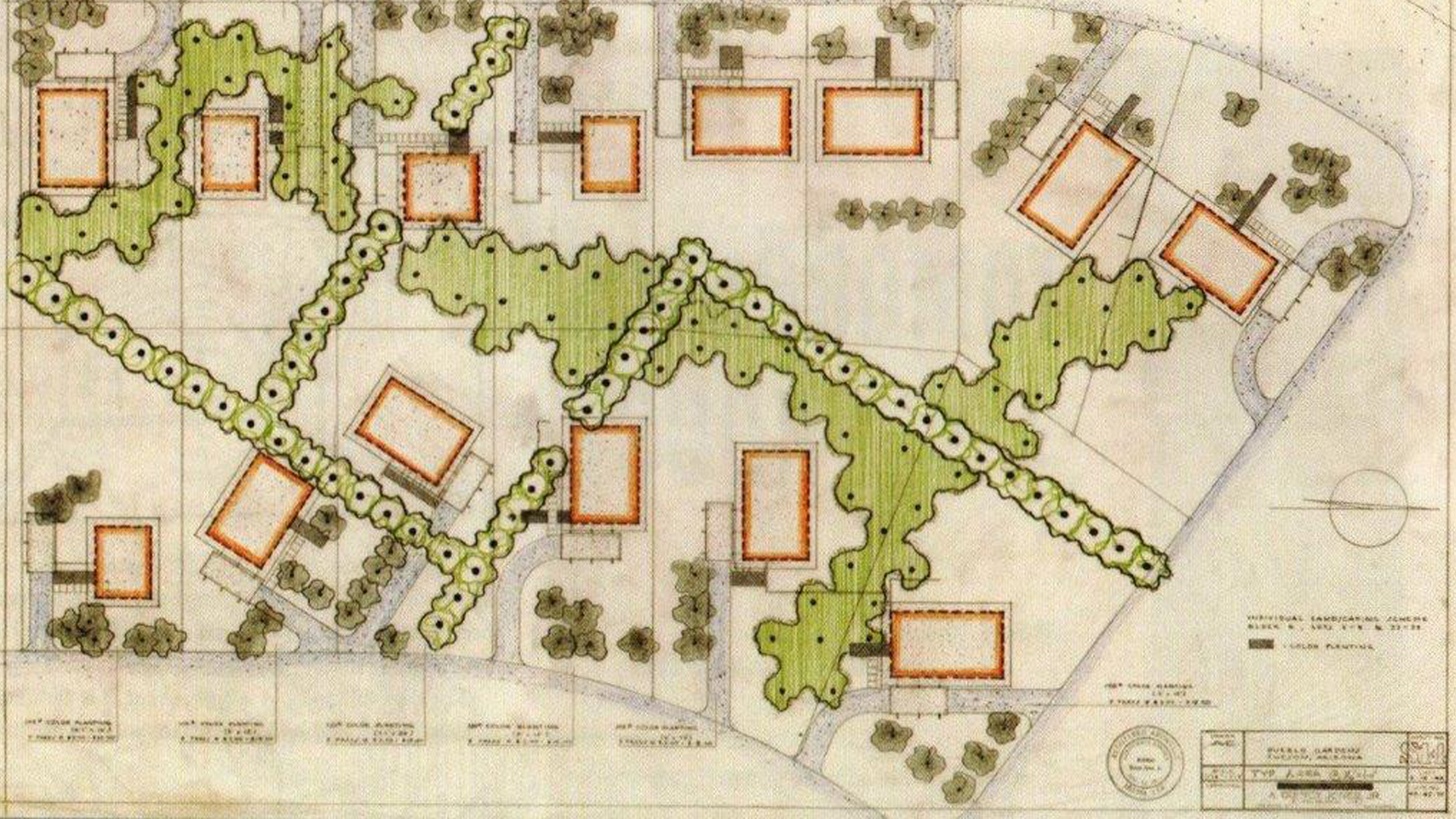

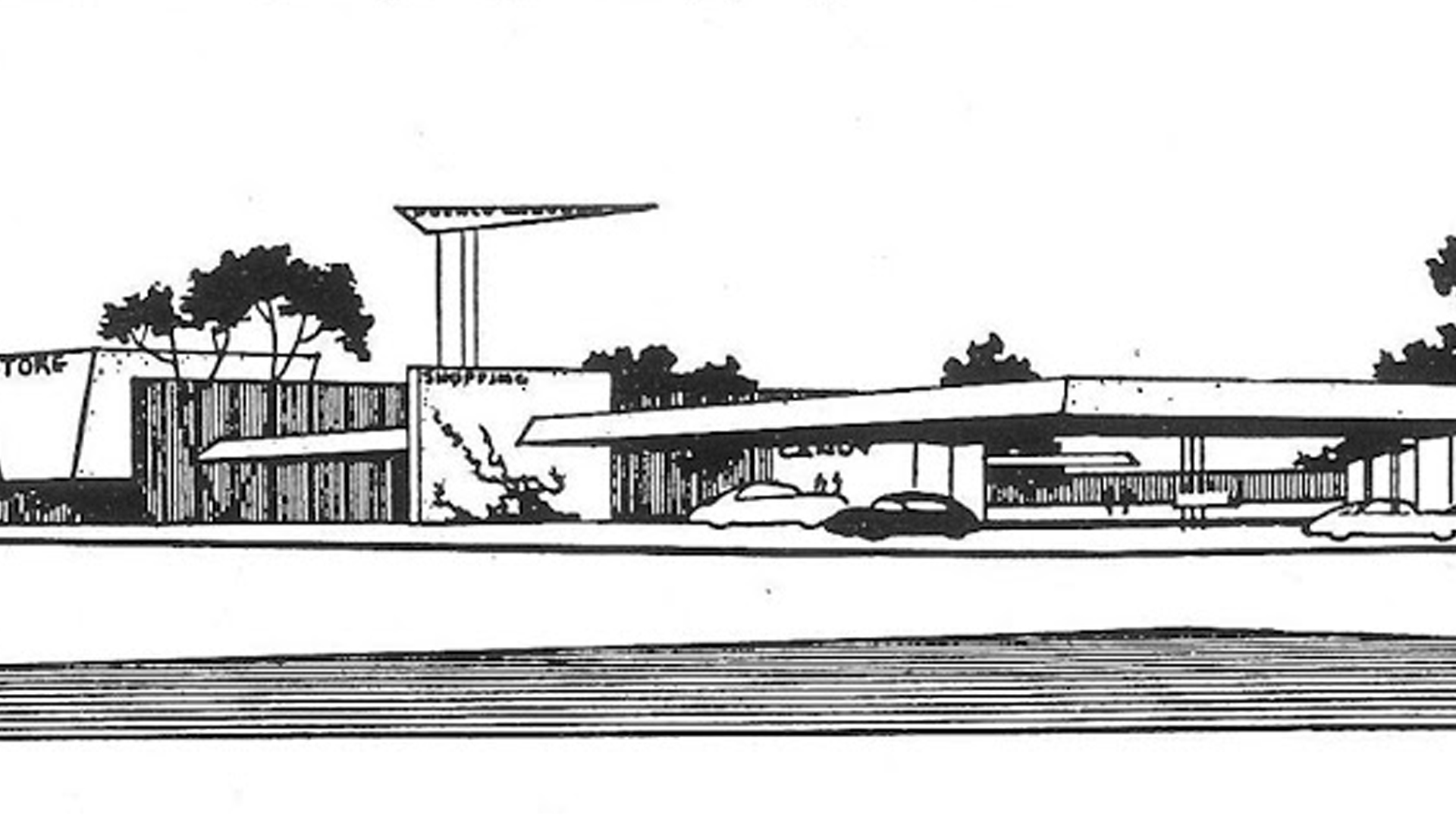

The neighborhood is designed as a grid, but within a triangular piece of land. The diagonal perimeter roads were dubbed ‘Stravenues’ rather than ‘streets’ or ‘avenues’ and that is how their signage reads to this day (Stewart E4). Houses were sited on lots with varying setbacks and to orient with the path of the sun. Exteriors were California redwood combined with plywood or stucco painted with bright desert colors. Jones developed an overall landscaping plan including planting Eucalyptus for wind and light control, olive trees for shade and oleander to control dust (McLain 33). Webb also included plans for a $2.5 million neighborhood one-stop shopping center, Pueblo Plaza, also designed by A. Quincy Jones (Walker E1).

Unfortunately, poor sales of the homes limited the development to 750 homes. After selling 170 homes, Drachman bought the rest from Webb. He lowered the prices, but ended up turning over 300 over the unsold units to the Federal Housing Administration. Plans for sidewalks, streetlamps and sewers were abandoned (Walker E1). In a draft for her Tucson Post WWII Context Study (2007), Abele noted that the first post-war boom peaked in 1948. A brief local recession occurred in 1950 with the closure of the Consolidated-Vultee Aircraft Corporation plant (Abele, 22). Jim Turner, of the Arizona Historical Society offered several other explanations for the failure of Pueblo Gardens. “ Builders worked like crazy to catch up with the demand, starting in 1946. I bet that by 1950 they pretty much caught up with the shortage demand.” There was also a shift from development of the south-side to the east-side of Tucson. Finally, “Del Webb may have overextended himself, as he had lots of projects in Phoenix and Las Vegas in those days.” (Turner).

In 2002, Willie Bean, a longtime resident of Pueblo Gardens, led an effort to have the neighborhood placed on the National Register for Historic Places. Plans were made to circulate questionnaires to gauge interest in the neighborhood as well as to make a preliminary evaluation of the integrity of the homes.

Still, even without NRHP listing, the community has demonstrated an appreciation for its history. The neighborhood boasts of having the city’s first, and oldest neighborhood association in existence (Christopher). Like Levittown, the neighborhood held a celebration and parade for the 50th anniversary of its founding. Past Neighborhood Association president James Christopher still has the commemorative postal cancellation stamp designed for the occasion by children at the local school, although he is equally proud of the neighborhood’s annual Martin Luther King breakfast. Ironically, the original deed restrictions for Pueblo Gardens limited the purchase or occupation of the homes to persons of “…white or Caucasian race” (Webb, 1, 323).

Pueblo Gardens was one of 311 new developments started in Tucson, AZ during the post WWII period from 1945 to 1973 (Abele 21). After abandoning Pueblo Gardens unfinished, Del Webb went on to become one of the most successful development companies in the Southwestern United States. The character of Pueblo Gardens changed in the 1970’s as original owners moved out or put them up for rent. According to the 1990 census, 31.8 percent of the homes had become renter occupied units.

Why does one neighborhood remain as built, one change and grow, and a third deteriorate? Economics. Del Webb may have misjudged demand or been at the mercy of a fluctuating economy when he began Pueblo Gardens, and time has not been kind to the neighborhood. In The same economic issues are determining factors in the preservation of post-World War II suburbs. Preservation begins at the local level. In Pueblo Gardens, the residents have other priorities: “We fought for sidewalks, for curbs and street lights. We never gave up. We had to fight for our children,” said original homeowner Joanne Baker Graham 12A).