Guy Greene | 1923 – 2003

Tucson Landscape Architect by Helen Erickson

Tucson Landscape Architect by Helen Erickson

Tucson Modernism, defined by clean, simple lines and a casual informality, captured the exuberance of the post World War II era. In the southern Arizona desert, this style has come to be known as Sonoran Modern, emphasizing regional materials, adaptation to the desert climate, and an indoor/out door living. Landscape architecture played a critical role in creating a southwest style, and one of Tucson’s leading landscape architects was Guy S. Greene. Born in Geneva, New York, in 1922, he served as a U.S. Army Air Corps navigator during World War II. Subsequently he attended Amherst College and Iowa State University, where he received a BA in Landscape Architecture in 1948. After graduation, he moved to Tucson to work with John Harlow, Sr., at Harlow Gardens.1 By the late 1950s his work appeared in national journals such as The New York Times,2 and by 1962 he was undertaking large-scale projects such as the golf course at Skyline Country Club in Tucson.

Twentieth-century landscape architecture had evolved as an interdisciplinary profession encompassing horticulture, architecture, ecology and urban planning. Led by innovators such as Garrett Eckbo,3 who drew inspiration from sources ranging from the arts to physical sciences and sociology, it was a profession well-suited to Greene’s wide-ranging interests, which included city planning and psychological inquiry as well as horticulture and design.

In 1966 Greene joined the Department of Horticulture at the University of Arizona, teaching landscape architecture and collaborating with such academic luminaries as Warren Jones, a passionate advocate for the use and development of native xeric plants. By 1972 there were thirty-eight undergraduates enrolled in the Landscape Architecture pro- gram and nine graduate students.4 A year later there were eighty-three undergraduates and twelve graduate students, and the name of the Department had been changed to the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture.5 By 1973 the Landscape Architecture program had been reviewed for state accreditation and had been accorded independent status within the Institute for Natural Resources of the College of Agriculture. As one of only two faculty members in Landscape Architecture, Greene was obviously a motive force in this development, and it was not surprising that he became the first chair of the program.6

In the course of his work at the University, Greene participated in a cooperative research project with Dr. Lawrence Wheeler, Professor of Psychology and Optical Science. Underwritten by the U.S. Forest Service, the goal of the study was to devise “methods of testing people’s preferences and responses to various environmental situations, either natural or man made.”7

During the same period, he was exploring a wide range of other interests, experimenting with in nity edge swimming pools8 and studying desert plants with his colleague, Professor Warren Jones.9 Greene excelled in planning as well as design, creating a master plan for Cottonwood, Arizona10 and the concept plan for the Santa Cruz linear park.11

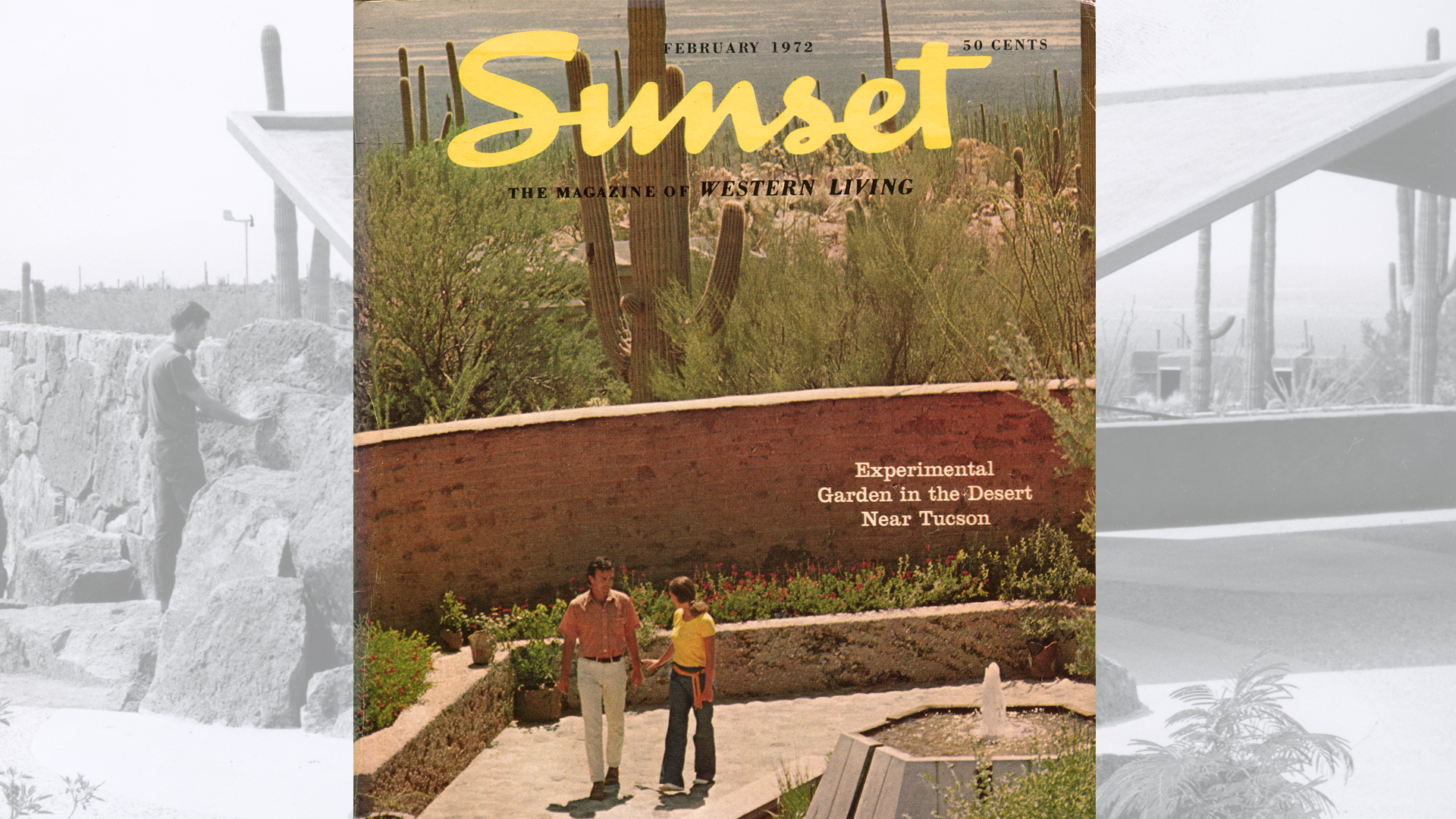

One of his most successful collaborations was with the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, located fourteen miles west of Tucson. In 1958 Sunset Magazine had sponsored an initial experimental garden in Arcadia, California, to demonstrate regional garden practice.12 In 1960 Sunset provided initial funding for Greene and the museum to design a series of exhibition spaces for native xeric native plants from the Sonoran Desert.13 The garden was to provide a source of ideas for Arizona homeowners by illustrating the use of a range of paving materials and by developing and testing useful plant varieties. The first section of the garden was completed in 1963,14 to be celebrated in the May issue of Sunset Magazine.15

This initial section of the garden is dominated by a hyperbolic paraboloid ramada of poured reinforced concrete. Under this shade structure is a naturalistic rock water feature inserted into a retaining wall. During rain events this is fed by rainwater collection from the roof of the ramada. Moving down the slope, a second section of the garden is reached by a paired set of stairs and a ramp designed to provide “wheelchair access”. The diversity of hardscape materials offers a number of options for construction, including stone, poured concrete and several types of pavers. Unlike the trees, which were intended to be long-term structural features of the design, planting areas were to provide space for experimentation with new cultivars as they became available.

A second section of the garden was completed in 1971.16 Linked by steps and a ramp to the upper areas, the new “Mexican Garden” included a geometric fountain with tile inserts made by Nathan Perlman and a traditional Tohono O’Odham ramada. Local Yaqui Indians created a curved wall of mud adobe to function as a windbreak against the open desert. River rock paving owed from the area around the fountain into a shady retreat surrounded by palms. Large concrete containers were fashioned by Jack Hastings.17

The Sunset Garden provided Greene with a demanding site, set on a steep incline. Taking advantage of the topography, he designed a sequence of garden rooms that ow from one level to another, linked by paired stairs and ramp. For the visitor, the result is a journey through space enhanced by the native plantings that the garden was designed to accommodate. On the warmest of desert days, it offers a shady oasis enhanced by the soft sound of desert water.

NOTES

1 Blake Morelock, “Landscape Designer Had Jobs Worldside,” Tucson Citizen June 6, 2003.

2 “Private Swimming Pools Now within Reach of Moderate-Income Families,” The New York Times June 20, 1959.

3 Eckbo (1910-2000) developed a theoretical basis for the practice of twentieth-century landscape architecture. He advocated for the integration of the arts, science and democratic social practice. Greene’s work incorporated these principles.

4 Anson E. Thompson, “Department of Horticulture: Summary of Highlights of President’s Report 1971-1972,” (University Arizona, 1972).

5 “Annual Report for the College of Agriculture 1972-1973: Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture,” (University of Arizona, 1973).

6 “Annual Report for the College of Agriculture 1973-1974: Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture,” (University of Arizona, 1974), 10-11.

7 Anson E. Thompson, “Research in Landscape Architecture,” (Tucson, AZ: College of Agriculture and School of Home Economics, The University of Arizona, [1973]).

8 See photo in ibid., 8. It has been suggested, but not substantiated, that Greene invented this type of pool.

9 Ibid., 11.

10 Guy S. Greene, A General Plan for Cottonwood, Arizona (1967).

11 “Santa Cruz Riverpark Master Plan,” (City of Tucson, 1976).

12 The Sunset Garden is part of a larger post World War II cultural phenomenon of magazine-sponsored design, of which the Case Study houses sponsored by Arts and Architecture Magazine

are perhaps the best known. In these projects architects and landscape architects created model houses and gardens that to serve as models for the general public.

13 [Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum], “Proposed Desert Museum – Sunset Magazine “Demonstration Desert Garden” at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, Tucson Mountain Park, Tucson, Arizona,” (1960).

14 Gene Brooks, “Desert Garden Ready,” Tucson Daily Citizen May 4, 1963.

15 Sunset Magazine, “The Desert Museum and Sunset Co-Sponsor a New Demonstration Desert Garden,” (May 1963).

16 “Last of Museum Garden Dedicated,” Tucson Citizen November 1, 1971; Sunset Magazine, “The Desert Museum and Sunset Co-Sponsor a New Demonstration Desert Garden.”

17 “The Desert Museum and Sunset Co-Sponsor a New Demonstration Desert Garden,” 118.