Desert Ad Men: Erni Cabat and Norval Gill

The Forgotten Legacy of the Cabat-Gill Advertising Agency

The Forgotten Legacy of the Cabat-Gill Advertising Agency

The year 1945 heralded a sea-change in the desert culture of Tucson, the Southwest, and the United States. Modernism had already taken root in the years between the World Wars. European intellectual and creative leaders began fleeing fascism for America. Bauhaus had arrived in Chicago in 1937, and with the entry of this German design philosophy, the avant-garde international style began seeping into the consciousness of the county, priming America for a design revolution. As the United States emerged from the WWII, new conceptions of art, architecture and graphic design were coursing across the American cultural landscape. A new visual lexicon was taking hold, based on Americans’ discovery of the world abroad.

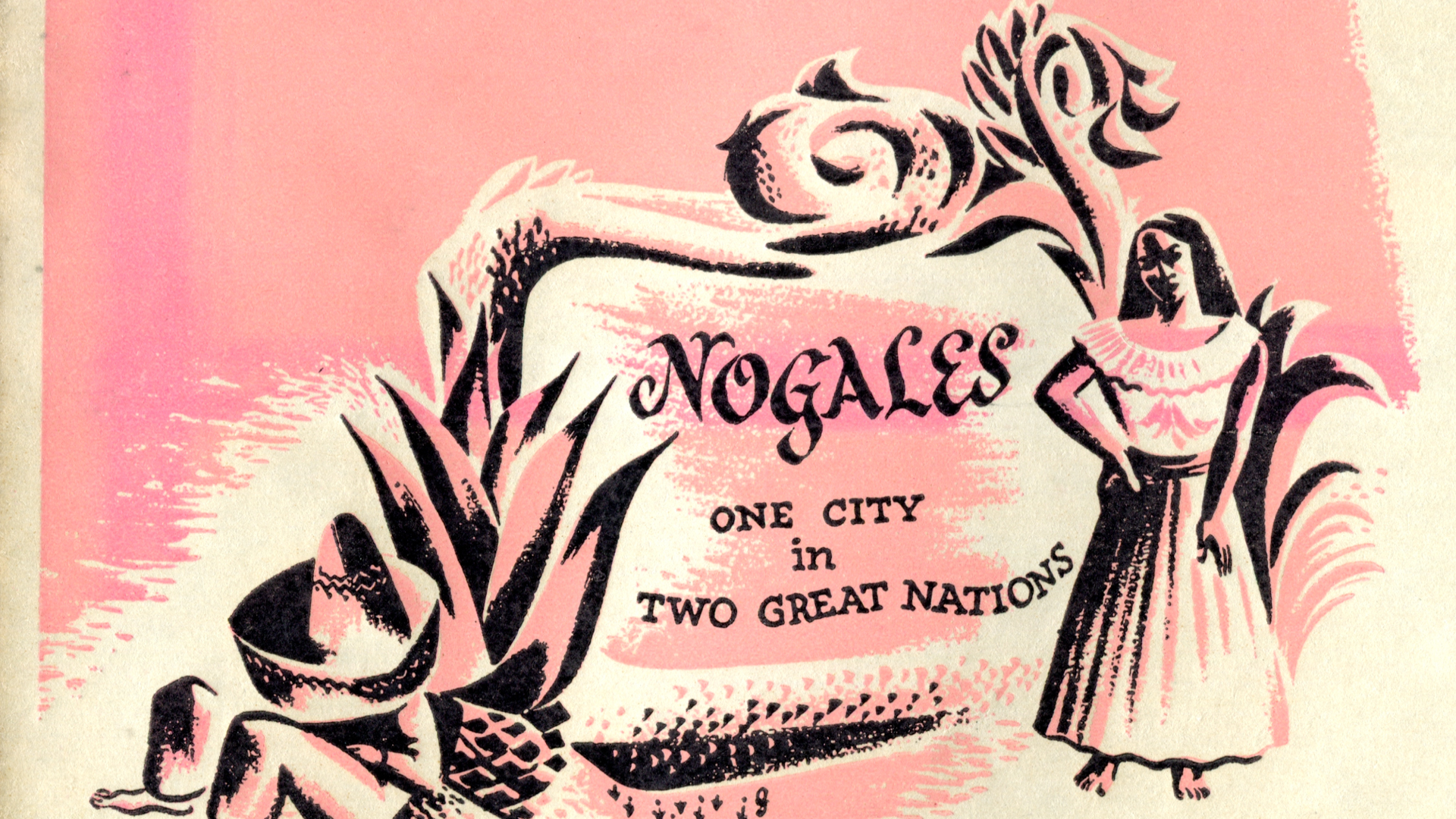

A new world opened up at home, too, along highways to the sunny, inviting and exotic Southwest. Featured in this issue are two leaders of our region’s economic advances in tourism. Cabot-Gill advertising created a new visual language highlighting the color, character and charm of the Southwest, and spread it throughout the country in tourism advertising. Post-war Tucson grappled with its identity. The cultural milieu of the American southwest was a paradox, both blending with and grating against idealized “Western” stereotypes and their visual vocabulary. This struggle to reconcile old and new yielded a unique regional aesthetic that teetered on the edge of kitsch.

When Ernest “Erni” Cabat and Norval “Joe” Gill opened Tucson’s first full service advertising agency in 1945, they broke from the stalemate with a clear focus on Tucson’s future. Their vision brought cutting edge, full-service marketing to Tucson, with an avant-garde visual sensibility that could carry traditional southwestern design elements into the space age.

Erni Cabat, born July 7, 1914, demonstrated a natural design talent. By the age of 20, he was freelancing for Columbia Broadcasting System, General Foods Inc., and Modern Packaging Magazine. His clients put him in charge of planning, designing and executing all types of advertising and promotional material. In 1933 he worked as an assistant to William P. Suther, head of design for Reynolds Metals Company. After three months, Suther put him in charge of the department. Three years later, Erni graduated from New York City’s Cooper Union Institute and married his childhood sweetheart, Rose. She would later become an icon of the modern American ceramics movement.

Throughout the great depression, Erni was securely employed by giants of New York’s advertising industry. As an art director, he developed innovative campaigns for J. Walter Thompson, Young & Rubicam and Benton & Bowles. He also worked as art director for a division of Time and Life Magazines, and in 1940 he joined The Hazard Advertising Corporation. From 1940 – 1941, he worked for the renowned and influential designer Henry Dreyfuss as art director in charge of industrial design projects. During this period, Erni managed a team of 14 designers to redesign a complete line of packaging (including labels, displays, cartons and eventually machinery) for the National Biscuit Co. (NABISCO). Somehow he also found time to study cartography and blueprints at City College in New York.

In 1942, Erni moved to Tucson and took a position with the airplane manufacturer Consolidated Vultee. Soon after, he began studying engineering principles at the University of Arizona. Consolidated Vultee is where Erni met Norval “Joe” Gill. Joe was born in Stockton, California in 1914. A skilled illustrator and watercolorist, he graduated from the California College of the Arts in 1937 with a degree in Arts Education. He worked for the New Deal Federal Arts Project, and as a night teacher at Hayward High, before moving to Tucson with his wife, Patricia Waltz, on New Year’s Eve, 1938. He was teaching at Tucson High School when the U.S. entered WWII, but he joined Consolidated Vultee to aid the war effort. Joe became supervisor of production illustration for the tooling department, working to help modify the B24. He was later promoted from the Industrial Engineering Department to supervisor of the Tooling Department.

As the war ended, Erni and Joe6 set up shop in Joe’s home on Prince Road along the bend in the Rillito River. The firm developed multi-faceted advertising campaigns including publicity, public relations, marketing, and media analysis. In announcing the new business, The Tucson Daily Citizen suggested that there was a “need in Tucson’s commercial development for improved and comprehensive methods of advertising and merchandising,”

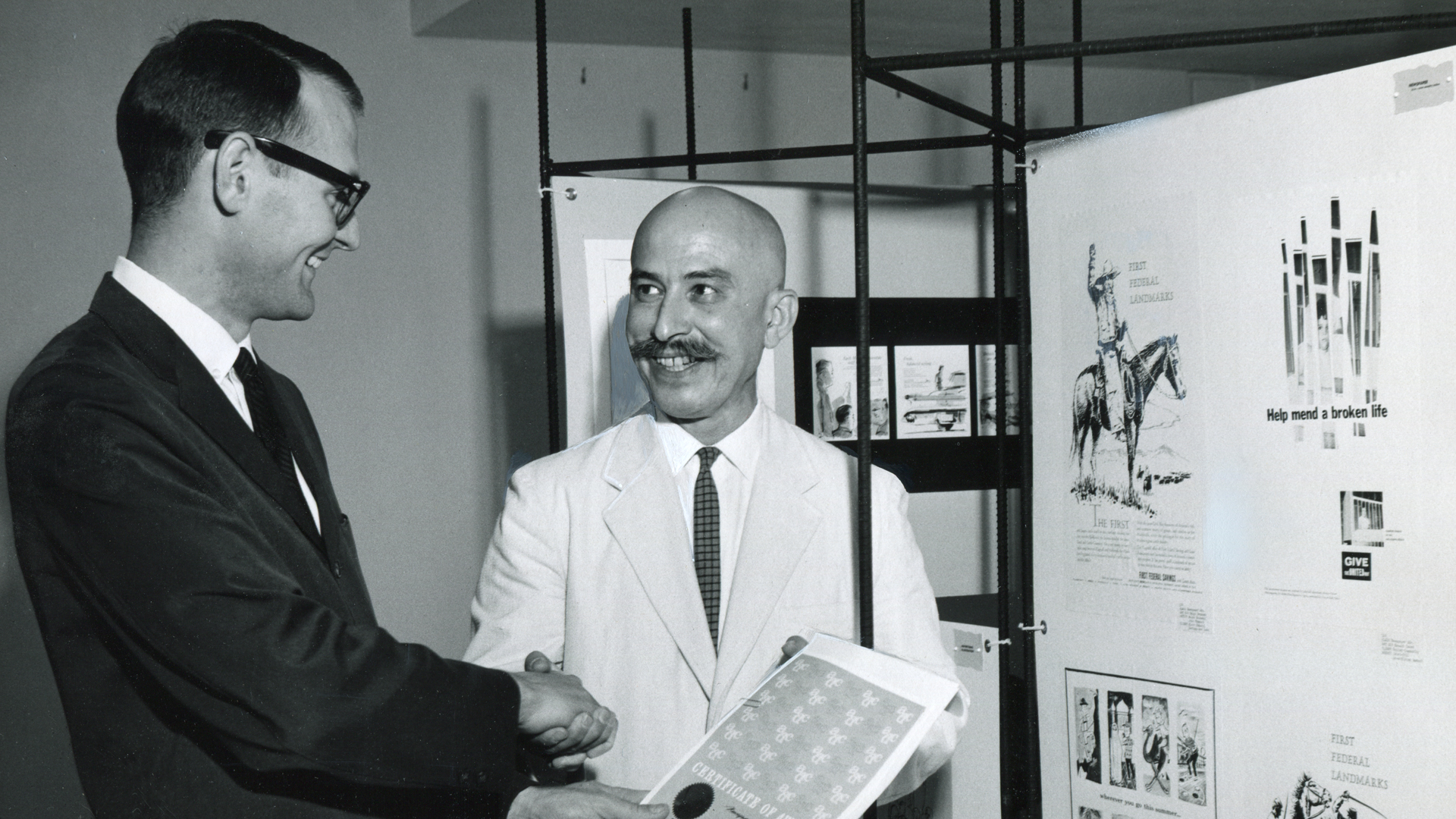

In 1948, Cabot-Gill moved to 87 East Alameda Street. Throughout the late 1940s and 1950s, with Erni as creative director, the firm won numerous local, state and national awards. Their work was shown throughout the west, published in books, and reproduced in trade publications. They won top awards from the Advertising Association of the West year after year, and won the bulk of local annual advertising awards.

In 1950, Joe left the partnership to move to Los Angeles, forming a new firm, Studio G, with Alan Grant. In the 1960s and early 1970s, Studio G developed work for Max Factor, Baskin-Robbins, Carnation Foods, Sizzler and ARCO among other national brands. Erni remained in Tucson and became the sole partner and creative director of the agency, which kept its name.

In 1952 Erni moved the firm to 194 North Church Avenue. The agency continued to grow, becoming the premier advertising agency in Southern, Arizona. In 1953, at the Phoenix Ad Club’s statewide “Annual Advertising Awards”, Cabat-Gill won 1st, 2nd and 3rd prizes for both the “Most Outstanding Service or Product” and “the Most Outstanding Direct Mail Campaign.” They also won the top three awards in “Transit Advertising”.

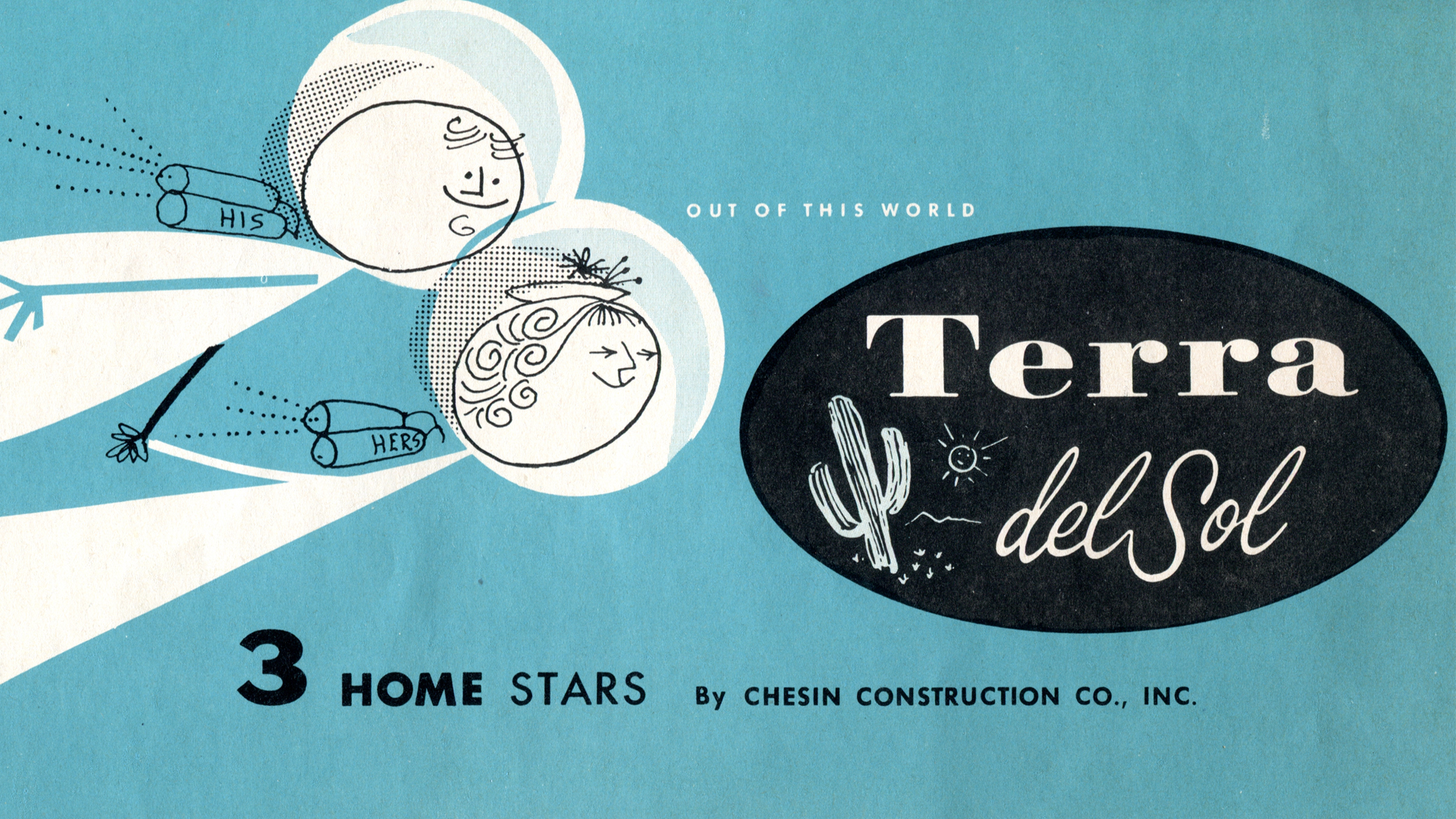

Cabat-Gill’s long list of clients covered more than a dozen regional organizations, including Northern Mexico, the Phoenix Chamber of Commerce, and the Tucson Sunshine Climate Club. Commercial clients included such local institutions as Southern Arizona Bank and Trust Company, Pima Realty, Harlow Nurseries, Levy’s and Steinfeld’s department stores, The Tucson Biltmore, Le Cave’s Bakery, The Flamingo Hotel, Pioneer Paints and Varnish Company, KOPO TV, Burger Square, American Homes, Lusk Homes, Casa Adobes Estates, Tucson Land and Development Company – Wilshire Heights, Wickenburg Sun Ranch, Rancho De Los Caballeros, and numerous other guest ranches.

Cabat-Gill was an early booster of local TV. By mid 1952, when Tucson was 86th on the FCC list of cities applying for broadcasting permits, the firm began positioning itself for participating in the new media market. During the summer of 1952 Erni traveled to research “big time T.V. advertising” at TV studios, agencies and TV film companies in L.A. and New York. On February 1, 1953, KOPO began the first local TV broadcast in Tucson. Just over a month later, Cabat-Gill had created more than 71 TV productions, ranging from 60-second spots to 15-minute live shows. That June, with Horace J. Landay Productions, Cabat-Gill began producing the weekly local quiz show “Beat the Winners.” It debuted a month later.

The agency employed a noteworthy cast of talent. Howard Bettersworth, Director of the Art Department, had been a highly successful commercial artist in New York, working for Bigelow-Sanford Carpets, McCall Magazine, Phelps-Dodge and U.S. Steel. Well-known local artist Stan Fabe worked in the office creating graphics. Other staff included Sally Schloss, Natalie Ziprin, Su Plummer, Marge Duke, Barbara Curtiss, Helen Wiegmink, Jan Jasperson and Norman H. Tripplehorn.

In 1957, the agency moved to 627 North 4th Avenue, a stand-alone building with exterior details designed by Charles Clement. As the firm wound down in the late 1970s, the building became Cabat Studio, a production and gallery for Erni and Rose’s Ceramics and Art.

Erni believed in good design and worked to train a generation. In 1948 at Tucson High School, he began teaching a creative approach to advertising design. Just five years later, he was providing cutting-edge marketing tools to students at the University of Arizona. Besides fundamentals of advertising, promotion and marketing, Erni taught color theory and psychology, layout and design, marketing and media analysis, budget planning, control, and basic design. He also led popular creativity workshops. At Iowa State College in Cedar Falls in 1966, he taught summer classes. In 1972, he partnered with the United States Information Services to present creativity workshops in Iran and five Brazilian urban centers. Working with the International Executive Services Corps, he taught basic design, hand crafts, and product advertising at the Tehran School of Social Work in Iran.

Erni was member of the Tucson Fine Arts Museum, Tucson Craft Guild, Arizona Designer Craftsman, and the American Crafts Council. He was also a charter member of World Crafts Congress and represented Tucson in the conference in 1964, 68, 69 and 74. He was member of the Southern Arizona Watercolor Guild, The Arizona Artist Guild, the Palette and Brush Club, the “Group”, and The Arizona Watercolor Association. His professional memberships included the Alpha Delta Sigma advertising fraternity, the Tucson Advertising Club, Advertising Association of The West, and the American Federation of Advertising.

Erni and Cabat-Gill helped usher in the age of local television advertising, promoting guest ranches, launching shopping centers, marketing housing developments, all with an eye toward local identity. With national campaigns that promoted the region, Cabat-Gill was instrumental in defining the distinctive brand and identity for mid-century southern Arizona and the southwest. America’s current fascination with its mid-century culture has drawn new fans to Cabat-Gill’s artistic adaptations of saguaro cactus silhouettes, cattle brands, Mexican and Native American motifs, biomorphic shapes, abstract graphics and array of desert hues — pinks, turquoises, umbers, oranges and yellows. That ageless visual language still weaves a sun-drenched spell with the lore and the loveliness of our Southern Arizona Home.