Charles Bolsius (1907–1984), Carolus Godefridus Wihelmus Marianus Bolsius was Dutch-born artist and craftsman, who left a lasting mark on Tucson through his artwork, woodcarving and architectural design at Old Fort Lowell. Working alongside his sister-in-law Nan Bolsius (1892–1963) and brother Adrianus “Adrian” Antonius Peter Maria known as “Pete” (1897–1987), Bolsius transformed the ruins of the abandoned military post into a unique compound that married Pueblo and Spanish Colonial revival traditions with handcraft and artistic invention. His architecture, like his woodcarving, reflected a commitment to historical continuity, material authenticity, and personal artistry.

-

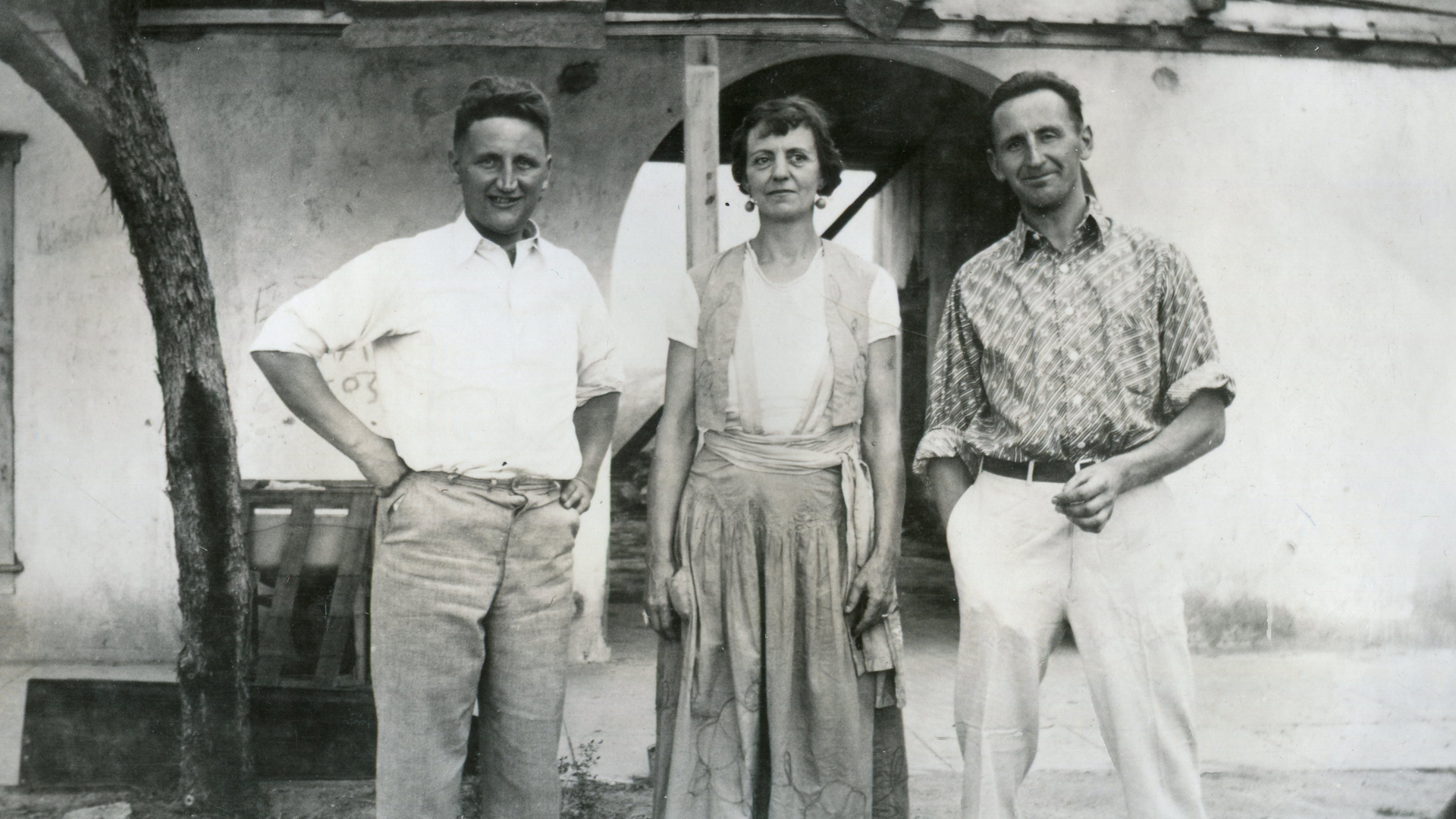

Charles Bolsius at work with Nan and Pete Private Collection

Charles Bolsius at work with Nan and Pete Private Collection

When the Bolsius family acquired the crumbling Sutler’s Store at Fort Lowell in the 1930s, the structures had been long abandoned since the Army left in 1891. Newspaper accounts describe how Charles and his family rebuilt the adobe walls by hand, scavenging beams from abandoned railroads and mines, and fashioning doors, windows, and fireplaces with tools they often improvised themselves. This process of reclamation was central to Bolsius’s philosophy: to use available, weathered materials and imbue them with new life through design and carving. The result was a hybrid of preservation and reinvention, where historic ruins became the foundation for a new creative environment.

-

Bolsius Family, Nan, Pete and Charles, c. 1935 Private Collection

Bolsius Family, Nan, Pete and Charles, c. 1935 Private CollectionFor Bolsius, architecture was inseparable from handcraft. Every door in the building was carved with a different motif, each fireplace built with distinct details, and even utilitarian elements such as cupboards and beams were treated as artistic surfaces. Unlike conventional revival-style architecture, which often relied on commercial reproductions, Bolsius’s designs were executed entirely by hand, giving the structures a tactile authenticity. Thornton Wilder, after visiting, commented on their resemblance to old English cottages, underscoring how Bolsius’s architecture fused European craft traditions with Southwestern vernacular.

The architectural vocabulary at Fort Lowell drew heavily from the Pueblo revival movement flourishing in New Mexico, particularly Santa Fe and Albuquerque, where Charles had spent formative years after arriving in America following his graduation from The Royal Academy of Art at the Hague. WPA initiatives in the 1930s promoted the documentation and revival of historic Spanish-Pueblo design, encouraging the use of carved wood doors, corbelled vigas, and thick adobe walls. Bolsius adopted these motifs but reinterpreted them in personal ways. His designs were not archaeological reconstructions, but living adaptations “peculiarly their own,” as the Arizona Daily Star observed in 1948, crafted from local adobe, hand-hewn timber, and carved ornamentation.

The Bolsius compound, known as Las Saetas (“The Arrows”), became both home and artistic statement. Visitors frequently remarked on the unity of architecture, furniture, and decorative arts within the space. The twelve hand-carved dining chairs, tin chandeliers, wool draperies, and hand-forged ironwork reinforced the idea of a “total work of art,” in which architecture was only one element of a broader aesthetic vision. The home became a cultural landmark, hosting exhibitions, fundraisers, and artistic groups such as the National League of American Pen Women, who praised its integration of handcraft into every architectural detail.

-

Las Saetas GM Vargas

Las Saetas GM Vargas Las Saetas fireplace, 1945 Photo by Bill Sears, THPF Collection

Las Saetas fireplace, 1945 Photo by Bill Sears, THPF Collection

Bolsius’s career was interrupted by World War II. Serving in the European theater, he was part of the generation of artists and craftspeople whose work was defined both by prewar experimentation and postwar renewal. Returning to Tucson after the war, Charles rejoined his sister-in-law Nan in restoring one of the most significant structures at Old Fort Lowell, the dilapidated Commissary. They named the project El Cuartel Viejo (“The Old Barracks”), underscoring both its historic military origins and its rebirth as a cultural landmark. The meticulous reconstruction combined structural stabilization with the introduction of handcrafted details, linking preservation and innovation.

After completing El Cuartel Viejo, Bolsius turned his attention to his most personal project: the construction of his own residence, the Charles Bolsius House developed over three decades. Built in stages, the house reflected his evolving mastery of Pueblo and Spanish Colonial revival design and woodcarving. Every element, doors, staircases, ceiling beams, was hand-designed and often hand-carved. The house became an architectural laboratory where Bolsius refined the carving techniques rooted in his New Mexico experiences with WPA-style furniture revivals.

-

El Cuartel Viejo GM Vargas

El Cuartel Viejo GM Vargas

Bolsius’s final architectural project was the LeaChar House, built in the Tanque Verde Valley east of Tucson. Designed in a late Territorial Revival style, the residence was constructed of burnt adobe, a material closely associated with Tucson’s mid-20th-century architecture. As with his earlier work, the house featured hand-carved doors, woodwork, and custom details throughout. A screened Arizona Room incorporated the dismantled gate originally created for Las Saetas, an emblem of Bolsius’s tendency to repurpose and transform earlier works into new settings.

In addition to his residential projects, Bolsius produced a significant body of commercial work. His carved doors, furniture, and architectural details appeared in a range of Tucson homes. One of his most notable collaborations was with Veronica Hugart, a Fort Lowell neighbor, designer and craftswoman with whom Bolsius partnered on a variety of projects. Their combined work expanded the reach of handcrafted design in Tucson, pairing Bolsius’s carving with Hugart’s architectural design to create interiors that highlighted regional identity.

-

Chalres Bolsius, c. 1970 Photo by Bill Sears, THPF Collection

Chalres Bolsius, c. 1970 Photo by Bill Sears, THPF CollectionCharles Bolsius was not only a woodcarver and painter but also an architect in the truest sense of the word: a maker of built environments. Bolsius’s architecture reflected a lifetime commitment to craft, revival, and artistic individuality. His membership in Tucson art organizations ensured his skilled artistic voice was part of the city’s broader cultural discourse, but it was his hand-carved doors, beams, and furniture that left the most enduring mark. Bridging New Mexico’s WPA traditions with Arizona’s Spanish Colonial revival, Bolsius gave Tucson some of its most distinctive handcrafted architecture, spaces where history and artistry remain inseparable.

-