Swirling form and movement, applied in highly charged layers of tension, Nik Krevitsky vacillated between powerful figurative imagery and abstract work. He developed his artistic maturity at a pivotal moment within the evolution of American modernism. Through his expressive compositions, critique and, as art educator, influenced the regional modern movement of the American West and developed a multi-media fiber art process called Stitchery.

Nathan “Nik” I. Krevitsky was born in Chicago on February 9, 1914 to Russian Jewish parents Joseph and Ida Krevitsky. He graduated from the University of Chicago in 1935 with a bachelor’s degree and was awarded a teaching certificate from the Chicago Teachers College. The country, in the throes of the Great Depression, was only beginning to see signs of slow economic recovery. In April of 1935, Federal Government enacted the Work Progress Administration (WPA), a jobs program, which funded infrastructure projects and supported the arts including theater, music, literature and painting.

With few job prospects, the 5’6 tall, 138 pound, blue eyed Krevitsky signed up for participation in a Chicago dance project funded by the WPA. This introduction into formal movement tilted the arc of Krevitsky’s path pushing him towards the arts. He studied with the Chicago Repertory Theater and by 1940, the 26 year old was emerging as a distinguished dancer in the Chicago scene; the Chicago Tribune noted his participation in the Chicago Dance Council Annual May Festival at the Goodman Theater, pointing out that as part of the program, Krevitsky performed a solo dance “Where Is the Waltz of Vienna?”, and during the 1941 festival he performed a Modern expressive duet composition with Marjorie Parkin choreographed by Ruth Hatfield. The piece titled “These Are My People,” was loosely inspired by the poems of Langston Hughes and included an original score by Ihrke and Martin. The noted Tribune dance reviewer Cecil Smith assessed the Modern performance as “a self-conscious programmatic composition with the dancing having little to do with the literary subject matter.” Krevitsky worked as an art supervisor in the Chicago Public School system and illustrated books and publications for the board of education.

On the vanguard of Modern dance and with experience in teaching, Krevitsky was invited to join the faculty of Vermont’s Bennington School of the Arts in June 1941. The renowned dance program was founded in 1934 and headed by Martha Graham and included some of the most influential American modern dancers of the era: Hanya Holm, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman, Martha Hill, Erick Hawkins, Louis Horst, Norman Lloyd, and Bessie Schönberg. Krevitsky would remain connected to Graham throughout his life.

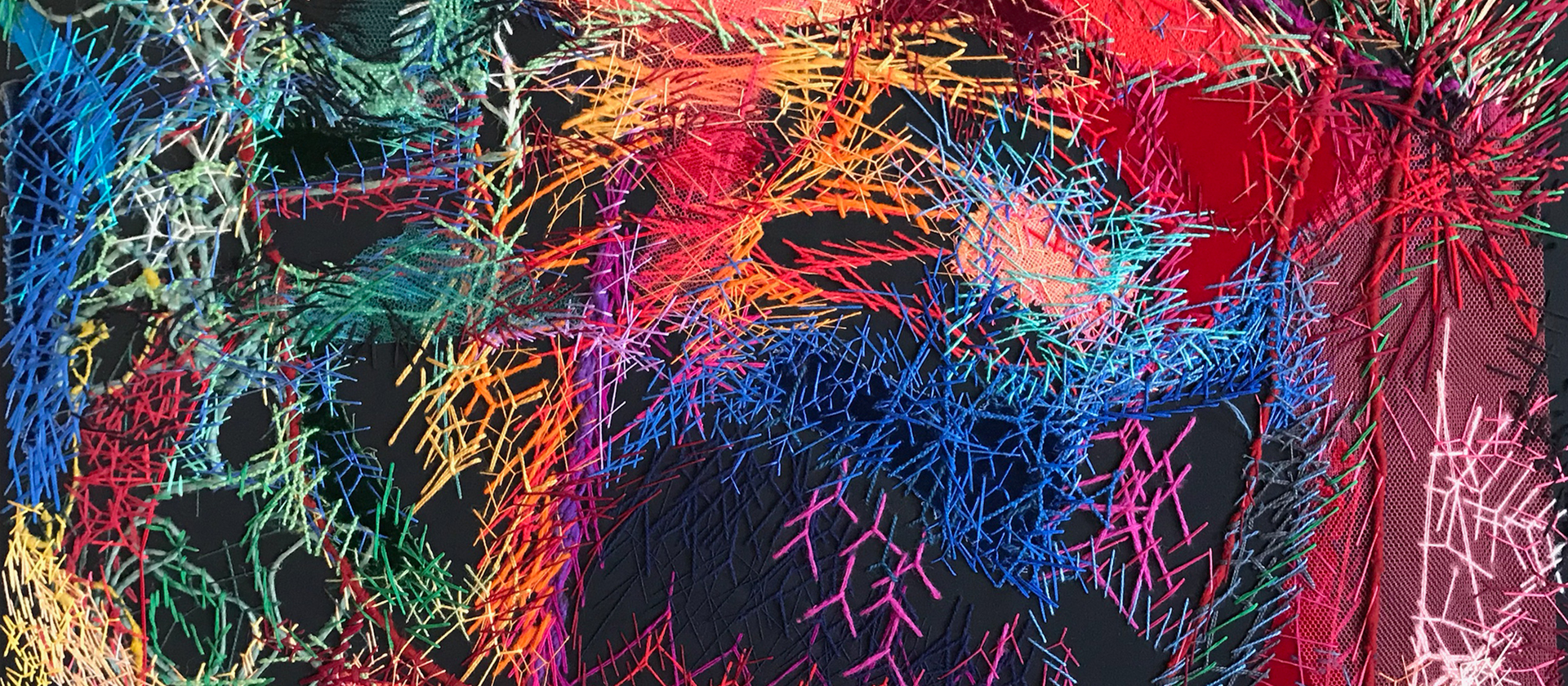

-

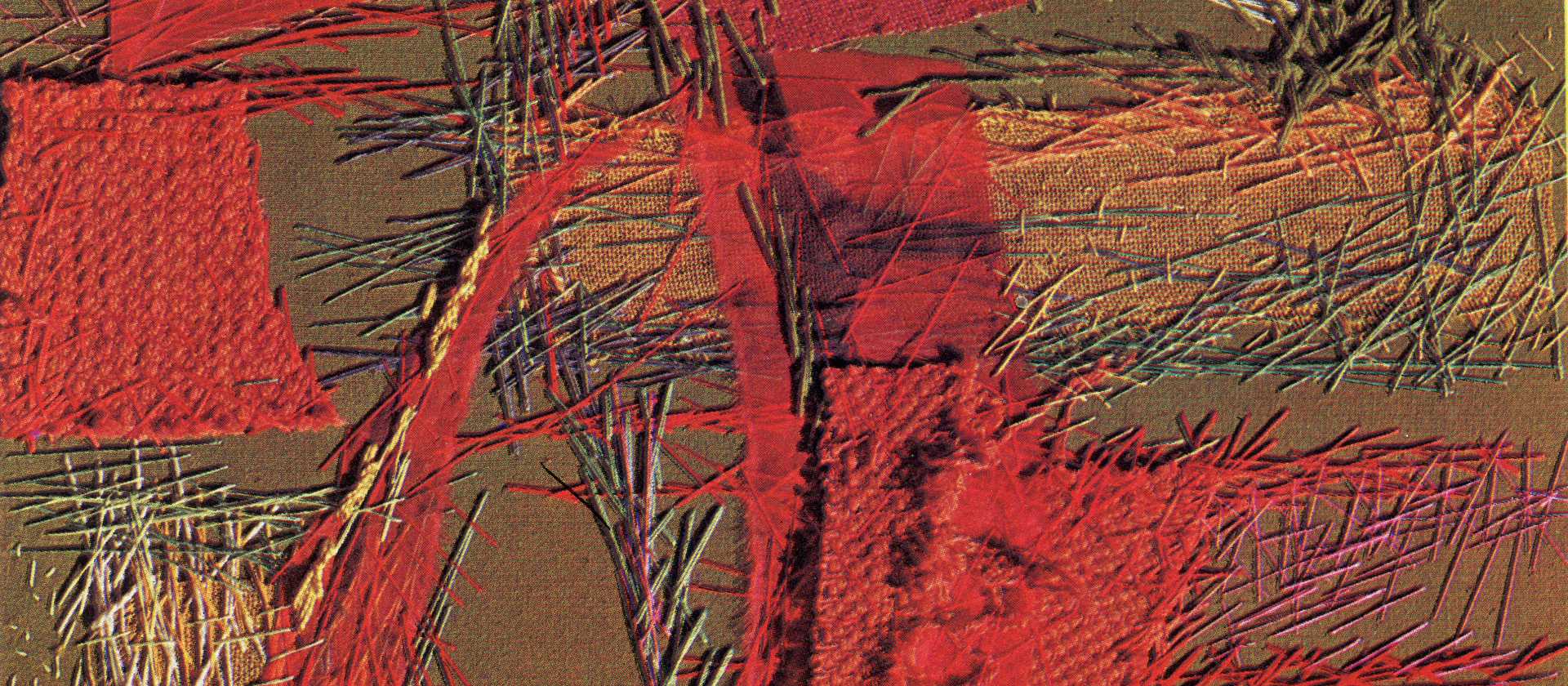

Nik Krevitsky Stitchery, c. 1965

Nik Krevitsky Stitchery, c. 1965He returned to Chicago in October to perform with Ruth Hatfield and Marjorie Parkin at the Cliff Dwellers. The recital included the dances: “Fallen Angel,” “Carry Us Back”, “Pavane,” and “Cake Walk.” In May of 1942, the trio choreographed and performed new original work with an original music composition by Katherine Hart at the Chicago Women’s Club. Titled “Dances to Poetry” and what the Chicago Tribune called “an important American sequence” called “These Our People,” the critic Cecil Smith noted “The dance […] was marked by intelligence, wit, and clarity of purpose.”

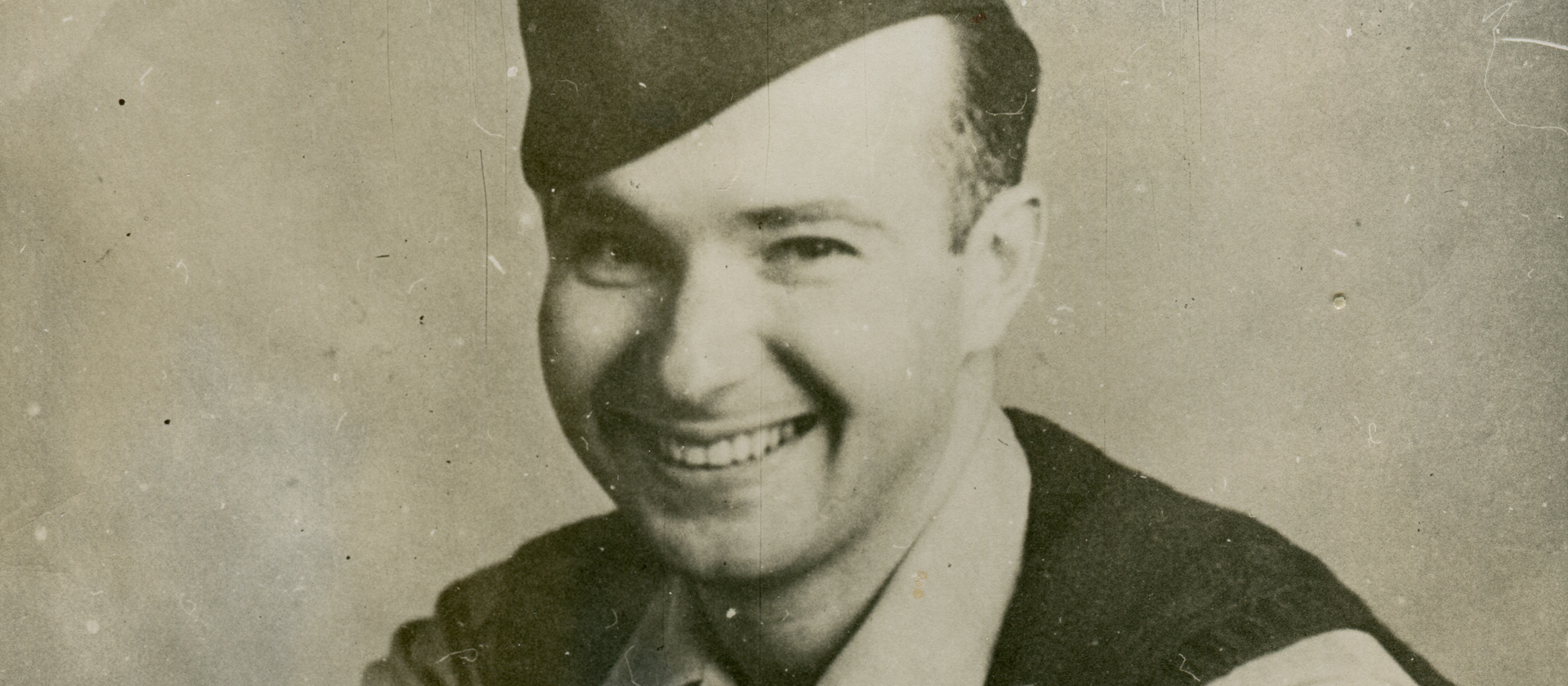

Within a month, in June of 1942, like most male dancers, Krevitsky joined the military. He enlisted in the Army as a branch Immaterial warrant officer as a Private. The Chicago Tribune reported that “former moving spirit of the Chicago Dance council [Krevitsky], became a soldier in June and now is the farthest corner of Alabama.” During the war, he designed posters and stage sets for the Army. He served with the 81st Infantry Division before being sent to California in 1944 take a special course in Chinese, Krevitsky again partnered with Ruth Harfield to perform “Takeoffs” as part of Berkeley University Army Student Training Unit revue in the Wheeler Auditorium to raise funds for the Red Cross.

Assigned to Camp Crowder, in southwest Missouri, he was charged with painting a portrait of commanding General Paul J. Mueller. Krevitsky served in the 7th Signal Training Regiment. And during any down time Krevitsky would sketch. “Instead of smoking a cigarette with the rest of the fellows I take out my notebook and make sketches. I work very fast and I’ve become quite prolific in the last few months. When off duty I’m in the projection booth of the recreation hall, an ideal studio because nobody ever comes up there.”

In June of 1944 he was given a solo exhibition at the Service Club No. 1, the first “one-man” art show in the history of Camp Crowder the show included 60 works water colors, ink and crayon sketches and drawings. According to newspaper clippings from the period, “Ballet and other predominating subject matters were chosen for their escape value.” September of 1944 he returned to Chicago and had a one-man exhibition of watercolors, pen drawings and oil paintings at the Cliff Dwellers Club.

-

Nik Krevitsky Stitchery, c. 1940

Nik Krevitsky Stitchery, c. 1940Returning to Chicago after the war, Krevitsky began expanding his creative interests into drawing and painting, developing a style based on formal movement inspired by dance. In January of 1947 he was given a solo exhibition at the Chicago Public Library. By 1948, he had moved to the Lower East Side of New York and matriculated into a graduate program at Columbia University and was teaching classes. In October, he exhibited Recent Drawings at Cyril Aronson’s Studio Gallery in Detroit. The Detroit Free Press, in the announcement of the exhibition, noted Krevitsky’s “background in Modern Dance – he has studied with Martha Graham […] is reflected in his drawings.”

In New York by the late 1940s, he was a critical contributor to the publication Dance Observer and served as an Editor by 1949 through 1958, producing reviews and critique. Living at 435 West 119 Street, his continued analytic and acute involvement in Modern dance continued to have significant impacts on his graphic art. In 1950, Krevitsky served as the chairman of the Film Committee of the National Art Education Association. During this period, he spent two years at New York’s New School for Social Research and worked as a freelance designer and artist on TV graphics.”

With an academic interest in arts education, Krevitsky organized a survey of craft education for the American Craftsman’s Educational Council in 1951 . The results were presented at the School for American Craftsman of the Rochester Institute of Technology and explored the place of crafts in general education.

Through his critical writing, artistic production, and civic participation Krevitsky became a figure within the cultural environs of New York and part of The New York School. His art work, splitting from convention, focused on movement and gestural form, and emerged squarely within the new Post WWII Abstract Expressionism.

As Harold Rosenburg wrote in his seminal 1952 essay American Action Painters,

“The painter no longer approached his easel with an image in his mind; he went up to it with material in his hand to do something to that other piece of material in front of him. The image would be the result of this encounter.[…] Here the principle, and the difference from the old painting, is made into a formula. A sketch is the preliminary form of an image the mind is trying to grasp. To work from sketches arouses the suspicion that the artist still regards the canvas as a place where the mind records its contents—rather than itself the ‘mind’ through which the painter thinks by changing a surface with paint. If a painting is an action the sketch is one action, the painting that follows it another. The second cannot be ‘better’ or more complete than the first. There is just as much in what one lacks as in what the other has. Of course, the painter who spoke had no right to assume that his friend had the old mental conception of a sketch. There is no reason why an act cannot be prolonged from a piece of paper to a canvas. Or repeated on another scale and with more control. A sketch can have the function of a skirmish. Call this painting ‘abstract’ or ‘Expressionist’ or ‘Abstract-Expressionist’, what counts is its special motive for extinguishing the object, which is not the same as in other abstract or Expressionist phases of modern art.”

The major artists of this movement included Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Lee Krasner, Robert Motherwell, William Baziotes and Mark Rothko. This artistic vanguard split from traditional conventions of subject and technique, embracing a new order in art, advancing bold inventions in pursuit of significant content.

During this period, Krevitsky continued to develop his expressionistic forms and while growing increasingly interested in the role of Craft as a fine art. In 1953, he conducted a study of crafts in general education for the American Craft Council and the Art Education committee of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. He joined MoMA’s Education committee, and served as a council member, with noted artists, designers and educators including: Victor D’Amico, Ruth Reeves, Hal Woodruff, Victor Lowenfeld and Edwin Ziegfeld.

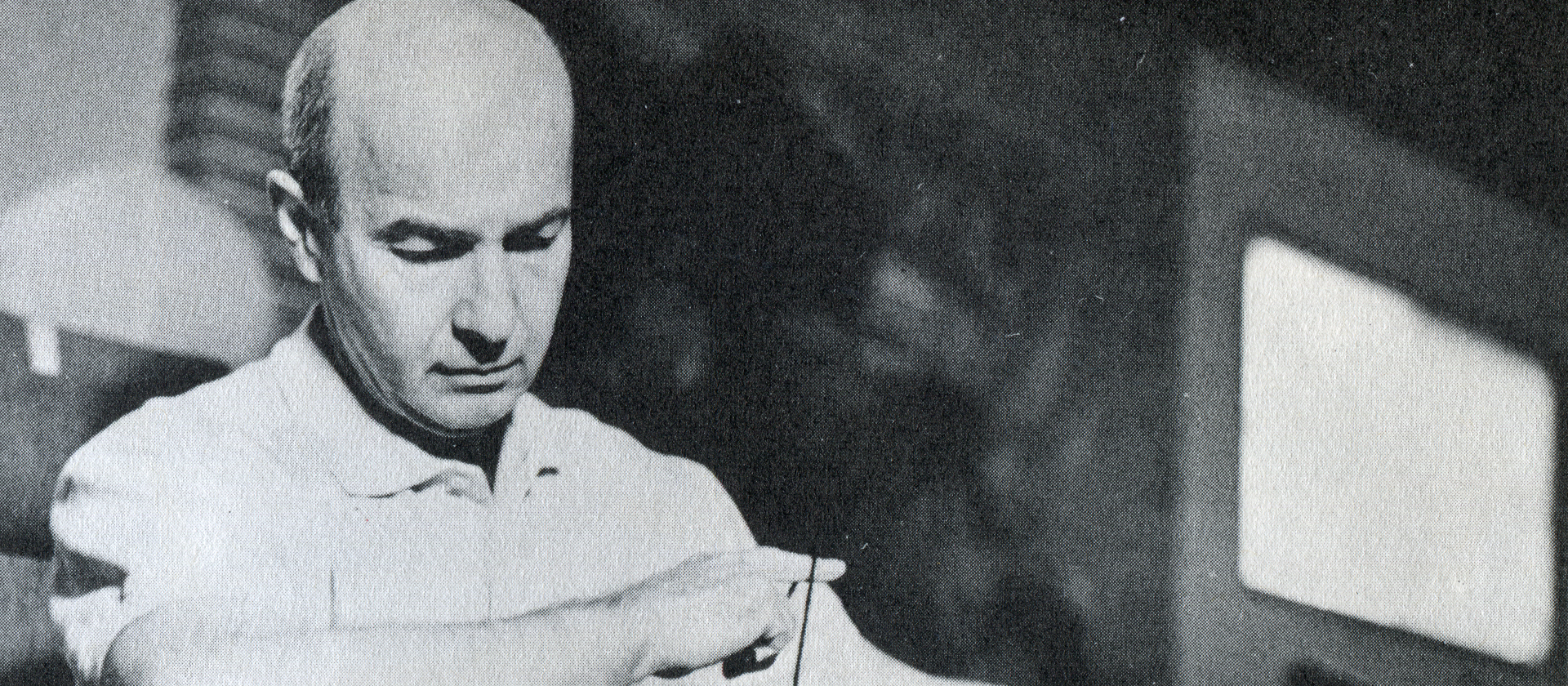

-

Nik Krevitsky, c. 1965

Nik Krevitsky, c. 1965While studying at Columbia University he worked as an instructor in design and art education at the Teachers College. He received his Master’s degree and Doctorate from Columbia in 1954. Before starting a position as a Visiting Art Professor at Goddard College in Vermont, he worked as a as an Associate Professor in the School of Fine and Applied Arts at Ohio State University, was an instructor at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York and published his first book Knifecraft.

In Vermont, outside of his college classes, he wrote as an art critic for the Burlington Free Press newspaper, and taught three-dimensional art classes for children and young adults at the Fleming Museum. During this period he began promoting the work of young artists, and in the fall of 1954, he took a position as a assistant professor of art at UCLA and moved to Los Angeles.

The West Coast and Los Angeles in particular was laid back. Ed Ruscha, who arrived in Los Angeles in 1956, reminced in an 2009 interview for the Guardian, “The 50s and the 60s were a very drowsy time. It wasn’t just a matter of piling paint on a canvas, as much as just living the life out here in LA. The movies were out here, the beach, the freeways, the desert. It had an accelerated pace to it; it was a fast city, but it didn’t have the cultural depth that New York had […] “

In L.A., Krevitsky, presented lectures, including participating in a panel discussion for the Westwood Art Association in March 1955 on the topic of “Art and Education Today,”, and with Mary Holmes, Ida May Anderson and Gibson Danes, offered a Children’s Workshop in the Arts in January 1956, focusing on color and texture in applied weaving with other UCLA art faculty Alma Hawkins and Martha Pollock. In April of that year, Krevitsky, presented a studio session and lecture at the fourth annual spring art studio and seminar at Minneapolis School of Art and presented a Symposium titled “Music and the Dance” with Anneliese Landau at the Los Angeles Westside Jewish Community Center in May 1956.

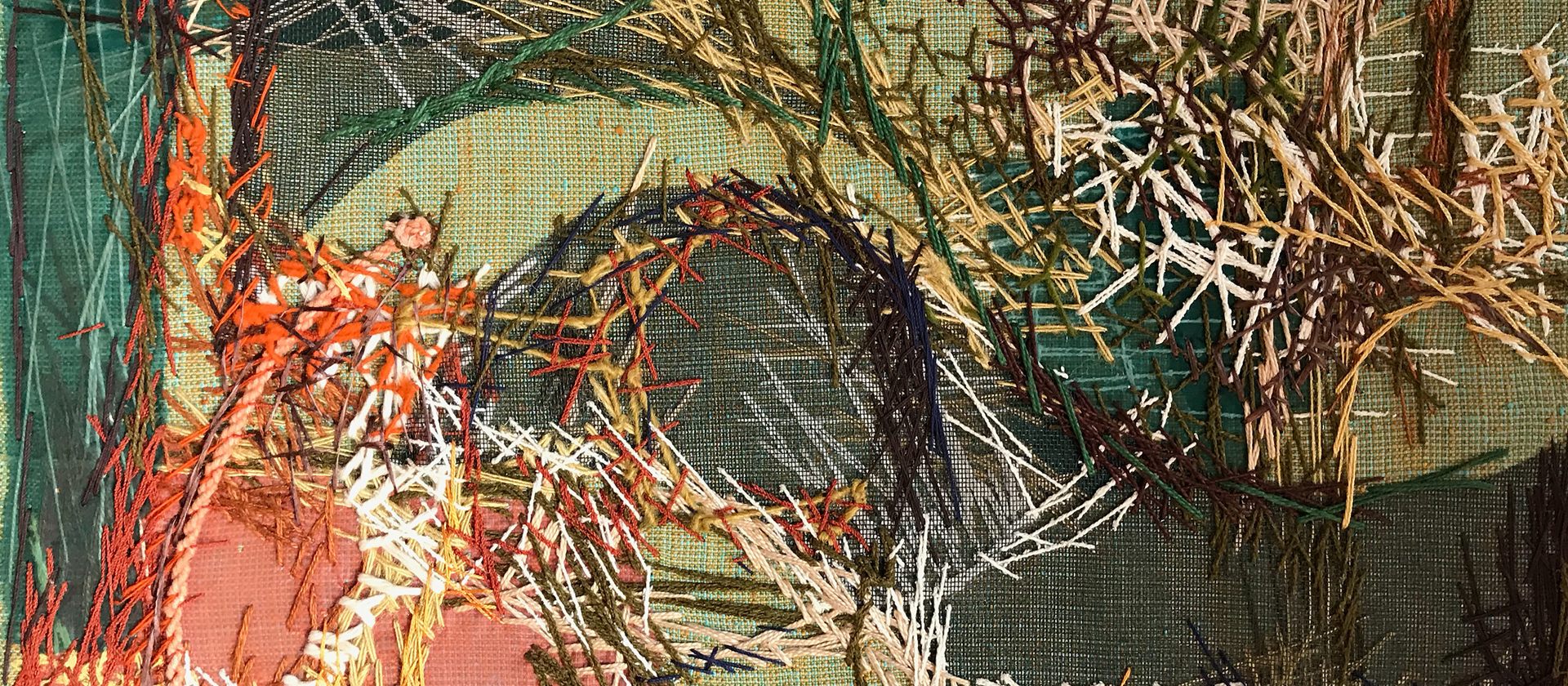

1956 was a watershed moment in Krevitsky’s artistic development. He began creating a fiber arts practice he called Stitchery. The work was fully Abstract Expressionist. Focusing on process Krevitsky leveraged the gestures of modern dance; the pieces were tensive and rhythmic. Layers of fabric and thread assembled on a frame through movement and form, compiled into an organic energetic work. The resulting spontaneous, improvised and dynamic multimedia, drew on craft traditions while fully aware of their time and place. The pieces were difficult to categorize in an era that favored the tradition of paint on canvas. Unlike his contemporaries in the movement who continued to push the bounds of painting, Krevitsky’s works were, at the same time, the canvas, the brush and the subject. This new work split from the traditions of convention, subject and technique, rejected representation, and embraced pictographic and biomorphic forms.

Over the next four years, Krevitsky would continue the development of this technique before formally showing these works.

In 1957, Krevitsky joined the faculty and served as art education instructor at San Francisco State College. In May of 1960 he produced and directed the Bay Area premiere of Stravinsky’s opera-oratorio Oedipus Rex at the Dinkelspiel Auditorium at Stanford University. The performance was produced with a full chorus and orchestra, using the Jean Cocteau text translated by e. e. cummings. The conductor was Sandor Salgo and starred: Patrick Dougherty, Irving Pearson, Robert Oliver and Nancy Cronberg.

-

Nik Krevitsky at work, c. 1965

Nik Krevitsky at work, c. 1965On 21 June 1960, Krevitsky was named as the Art Director for Tucson Public Schools, and moved from San Francisco in July 1960. He purchased a modern house at 5751 East 28th Street that he used as a studio. Throughout 1960, he participated in a number of group exhibitions, including “Arizona Designer Craftsmen” at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York, exhibited at American House, and showed with the “Arizona Designer Craftsmen Circuit” at the University of Arizona Art Galleries.

In the early 1960s, he was part of Tucson’s Workshop Center for the Arts with Berta Wright, Ruth Phipps, Hazel Archer, Barbara Johnson, Tina Russell, Eugene Mackaben, Charles Littler and Charles Clement. In early January 1962, he traveled to Hamburg Germany and participated as the sole US representative in a six day conference of the UNESCO Institute for Education focus on the the theme “Fostering Creative Expression and Critical Appreciation at School.”

In April 1962, Krevitsky presented the top “Is Modern Art Intelligible?” in Tucson, and in June of that year, Krevitsky served as a judge on the New Mexico Arts and Crafts Fair in the Old Town Plaza in Albuquerque and exhibited a solo show at the Workshop Originals gallery.

1963 was a busy year for Krevitsky. He was appointed to supervise the arts and crafts exhibition in the US pavilion during the month long International Trade Fair in Zagreb, Yugoslavia for the U.S. Department of Commerce. The American Crafts Council magazine Craft Horizons notated that “Versatile Nik Krevitsky is probably one of the busiest designer-craftsmen in the the Southwest” and was included in a Creative Crafts magazine article titled “Fabric Workers of Arizona,” featuring ten Arizona Craftsman eight of which where from Tucson, noting: “Encouraging a group of craftsman who are contributing immeasurably to the cultural development of the Southwest.” He was selected as the first exhibit for the new Arizona State College Gallery in Flagstaff and the one-man show was titled “Abstract Pictures with Threads”. After the month display in Flagstaff, the exhibit toured major galleries, colleges and universities in the western states.

In an interview with the Tucson Daily Citizen, Krevitsky said, “My stitcheries are appliqué and stitch panels – pictures, if you wish, but NOT paintings – which achieve effects not possible through other techniques or materials. They depend upon color mutations created through transparency, textural qualities of networks of threads and the use of various fibers and weaves.” Krevitsky based his abstract expressionist work on interpretations of representational themes. The Arizona Daily Star art critic noted in a 29 December 1963 article that “bold , flowing work which, as the artist has stated, has evolved from his entire experience. The work should prove intriguing and colorful. One must, when viewing it, follow the lines and areas of color and form to his conclusion, which has been in other shows a happy one.” Titles for the fiber work came from Krevitsky’s favorite poetry mood-inspired imagery which he transposed to stitched panels in vibrant pattern and colors” with names like: Geography The Government of Day, Meshes in the Afternoon and Efflorescence. “But names for the pictures are found to suit the finished work. The works are never created to fit a name. “Some of the works, including many six feet or larger in size, have luminous depths of color in translucent patterns with as many as 10 layers of stitches and materials. Surfaces vary from the smoothness of chiffon to the heavily-textured mass of layer-on-layer of wool fabrics. “If my work has meaning or gives pleasure to others, I have achieved what I want — to say something personal about my world which others may recognize as part of their world. Without communication, art has not purpose.” In the November/December 1963 edition of the nationally published Craft Horizon magazine, Krevitsky’s work was featured on the cover.

-

Nik Krevitsky Stitchery, c. 1968

Nik Krevitsky Stitchery, c. 1968In 1964 Krevitsky was appointed vice president and textile media chairman for Arizona by the American Craftsman’s Council in New York, and in 1965, Krevitsky purchased the deconsecrated San Pedro Chapel in Tucson’s Old Fort Lowell; that year, he converted the building into a residence, art studio and gallery. The same year, he was invited to present on stitchery at the Fifth International Congress of Esthetics in Amsterdam, Holland.

Like other major modernists designers, including Alexander Girard and Ray Eames, Krevitsky collected and celebrated Folk Art. In 1966 Krevitsky served as judge and curator for the New Mexico Designer-Craftsmen Show at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe (founded by Girard) selecting 108 works from 242 pieces submitted. As head of the Tucson Unified School District Art Department, he built an institutional teaching collection which included thousands of significant pieces folk art and hundreds of 20th century works on paper, including pieces by Lucio Fontana, and Mexican modernists.

In 1966, he published his first book:Stitchery: Art and Craft, though Reinhold Publishing, and continued to show throughout the United States. In 1973 he published Batik: Art and Craft, and in 1974, Shaped Weaving. In the late 1960s he served on the the editorial board of Impulse Magazine.

In 1974, he became the director of TUSD’s Thomas Lee Instructional Resource Center. He founded the Arizona Dance Alliance with former TUSD dance instructor Virginia Robinson. In August 1977, he retired from Tucson Unified School District. Throughout the 1970s Krevitsky taught workshops and gave lectures throughout the county and internationally.

-

Nik Krevitsky Stitchery, c. 1975

Nik Krevitsky Stitchery, c. 1975In the 1980s Krevitsky developed a new printing process he called sublimographs and were “achieved through heat transfer of disperse dyes previously painted upon paper sheets. Through controls of humidity, pressure, temperature and time various qualities are achieved.”

Krevitisly used the the process to produce “one-of-a-kind works, finding variations on a theme more satisfying then repeating identical imagers for an edition.”

Krevitsky died in 1991.

Over the course of his career, Krevitsky exhibited over 40 solo shows in major museums and galleries nationally and internationally, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Heard Museum in Phoenix, and the Tucson Museum of Art. He served and was associated with a number of national arts organizations including: Pacific Arts Association, American Craftsman’s Council, National Art Education honoraries Kappa Pi Phi, Delta Kappa and Kappa Delta Pi, and served as an advisor to MoMA, and the national arts and crafts program of the Girl Scouts. Krevitsky worked with the American Dance Festival at Connecticut College and the Arcosanti festival in Arizona.

Krevitsky was an important Abstract Expressionist who grew up in the mid 1930 to the 1940s within the modern dance movement in Chicago and alongside Martha Graham. He artistically matured in the New York School during the late 1940s through the mid 50s before moving to California. He pushed the bounds of fine art and abstract expressionism a trajectory away from painting into traditional craft pedagogy that ultimately resulted in narrow commercial success. Moving to Tucson in 1960 further limited his ability to change the national discourse on the definitions of fine art.

Krevitsky was classified not as a fine artist, but as a American craftsman. His avant-garde work was unquestionably on the leading edge, and despite being shown throughout the country and receiving critical praise between the mid 1940s through the 1980s, his pieces were accessioned into the collection of only a few museums. In a contemporary critical assessment of his work, Krevitsky was a fine art practitioner ahead of his time. His influence on fiber arts, art education, modern dance and the development of modernism in the Southwest was significant and viewing his work within this broader context shows an artist whose art captures the essence of American Abstract Expressionism.

Select Group Exhibits

1945 Artist of Chicago Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL

1946 Artist of Chicago Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL

1960 Arizona Designer Craftsmen Museum of Contemporary Crafts, New York, NY

1960 Group Show America House, New York, NY

1960 Arizona Designer Craftsmen Circuit University of Arizona Art Galleries, Tucson, AZ

1961 The Craftsman as Individual Arizona Craft Show / Art Center, Tucson, AZ

1961 Arizona Crafts ‘61 Tucson Art Center / Craft Guild, Tucson, AZ

1961 Contemporary Craftsmen of the Far West Museum of Contemporary Crafts, New York, NY

1961 The Arizona Designer Craftsmen Heard Museum, Phoenix, AZ

1961 Western Regional Show World’s Fair, Seattle, WA

1961 Applied Art Center Arizona State College, Flagstaff, AZ

1962 Group Show Workshop Center for the Arts, Tucson, AZ

1962 Arizona Crafts 1962 Tucson Craft Guild/Tuc. Art Center, Tucson, AZ

1962 Arizona Designer Craftsmen Exhibit Heard Museum , Phoenix, AZ

1963 Arizona Crafts 1963 -A Dramatic Accent Tucson Art Center, Tucson, AZ

1963 Artis as Craftsman – Craftsman as Artist Pavilion Gallery, Balboa, 1st biennial, LA, CA

1963 Grossman and Krevisky Yuma Art Center, Yuma, AZ

1964 Arizona Crafts 1964 Tucson Art Center, Tucson, AZ

1964 Western Craft Competition Exhibit Century 21 Center Inc. Seattle, WA

1964 Arizona State Fair Crafts Exhibition Arizona State Fair, Phoenix, AZ

1964 Artist-Craftsman Exhibition Westside Jewish Community Center, LA

1965 Arizona Crafts 1965 “New Concepts 1965” Tucson Art Center, Tucson, AZ

1965 Group Show Ruth Phipps Little Gallery, Tucson, AZ

1966 Arizona Crafts 1966 Tucson Art Center, Tucson, AZ

1966 Arizona State Fair Craft Show Arizona State Fair, Phoenix, AZ

1966 Fullerton Junior College Art Gallery Textile, Weaving and Rug Show, LA, CA

1966 Arizona Craftsman National Society of Interior Designers, SF, CA

1969 Group Show of Stitchery Oneonta Community Art Center, Oneonta, NY

1969 Objects: USA, the Johnson Collection American Craft Museum in New York, NY

1969 Contemporary Textiles Paine Art Center. Oshkosh, WI

1969 Group Show The Gallery for Contemporary Art, Tucson, AZ

1971 Objects: USA, the Johnson Collection Heard Museum, Phoenix, AZ

1971 Krevitsky & Grossman St. Philips in the Hills Gallery, Tucson, AZ

1972 International Craft Show Lubbock Art Association, Lubbock Texas

1972 Arizona Textile Exhibition Yuma Art Center, Yuma, AZ

1972 Members’ Exhibition Tucson Art Center, Tucson, AZ

1973 The Blanket Around Us Tucson Art Center, Tucson, AZ

1974 Arizona Outlook ‘74 Tucson Art Center, Tucson, AZ

1976 68 Contemporary Craft Objects Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE

1978 Krevitsky, Harris and Harris Kay Bonfoey Gallery, Tucson, AZ

1983 Krevitsky, Corona and Robinson Rosequist Galleries, Tucson, AZ

Select Solo Shows

1944 60 Works Service Club No. 1, Camp Crowder, Missouri

1944 Watercolors, Drawings & Oil Paintings Cliff Dwellers Club, Chicago, IL

1947 Works by Nik Krevitsky Chicago Public Library, Chicago, Il

1948 Recent Drawings Cyril Aronson’s Studio Gallery, New York, NY

1950 Dance Inspired Paintings U of Illinois, Festival of Contemporary Arts, IL

1962 New Mexico Arts and Crafts Fair Workshop Originals, Albuquerque, N.M.

1963 Colleges and Painting by Nik Krevitsky Tucson Art Center, Tucson, AZ

1963 Abstract Pictures with Threads Arizona State College Gallery, Flagstaff, AZ

1964 Nik Krevitsky Sedona Art Barn, Sedona, AZ

1964 Nik Krevitsky Nevada Art Gallery, Reno. NV

1964 Nik Krevitsky Roberts Arts Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

1965 Stitchery by Nik Krevitsky Botts Memorial Hall, Albuquerque, N.M.

1965 Painting Without Paint Tucson Art Center, Tucson, AZ

1966 Krevitsky Stitcheries University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA

1966 Nik Krevitsky Craft Alliance Gallery, St. Louis, MI

1966 Nik Krevitsky Stitchery Rosequist Galleries, Tucson, AZ

1966 Stitchery Community School, St. Louis, MI

1967 Stitchery Bewitchery of Nik Krevitsky Fresno State Gallery Art Gallery, Fresno, CA

1968 Cloth Collages Ball State University, Muncie, IN

1969 Painting with Thread, 40 Works Smithsonian, Washington, DC

1969 Nik Krevitsky Anneberg Gallery, San Francisco, CA

1969 Paintings in Thread Galleries Greif, Baltimore, MD

1969 30 Recent Works Gallery for Contemporary Art, Tucson, AZ

1970 Magic World of Color Tucson Art Center, Tucson, AZ

1972 Nik Krevitsky Stitcheries Yuma Fine Arts Association Gallery, Yuma, AZ

1972 Sitieries by Nik Krevitsky Mesa Community College, Mesa, AZ

1972 Stitchery Yavapai Community College, Prescott, AZ

1973 Stitchery by Dr. Nik Krevitsky Brookfield Craft Center, Brookfield, CT

1973 Abstractions 20 Works University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

1973 Fiber Stitchery by Nik Krevitsky Brookfield Craft Center, Bridgeport, CT

1974 Nik Krevitsky 40 New Works Hooton Gallery, Albuquerque, NM

1976 Galaxy Fresno Arts Center, Fresno CA

1977 Galaxies Bloomington Art Center, Bloomington, MN

1978 Three Dimensional Combinations Quad-City Arts Council Gallery, Rock Island, IL

1979 Fiber and Threads, Municipal Art Gallery, Davenport, IA

1985 Paintings Tucson Art Institute, Tucson, AZ

1986 Sublimographs by Nik Krevitsky Art Education Gallery, UMN, Albuquerque, NM

Films

Beginning Stitchery (Art Techniques Series) 3 ½ min. 8mm C-A Throne, 1966. Thorne Films

Selected Public Collections

Tucson Museum Of Art, Tucson, AZ

Museum of Arts and Design, New York, NY

The Henry Art Gallery, Seattle WA

Amphi Collection, Tucson, AZ

Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE

Books/Magazines

Editor, Dance Observer magazine.

Editorial Board, Impulse Magazine

Krevitsky, Nik, Stitchery: art and craft, Reinhold Pub. Corp., New York, 1966

Krevitsky, Nik, Batik: Art and Craft, Van Nostrand Reinhold Inc.,U.S., 1973

Krevitsky, Nik, Shaped Weaving, Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 1974

Krevitsky, Nik, Knifecraft, C.H. Hunt Pen Co. 1954

Freedman, Florence B. (illus. by Krevitsky), It Happened In Chelm. A Story of the Legendary Town of Fools, Shapolsky, , First Edition, 1990.

Freedman, Florence B. (calligraphy by Krevitsky), November Journey, 1973.

Creative Crafts, 1963 (January) or 1962. Fabric Workers of Arizona

Kelly; Evelyn Beard; Nik Krevitsky; Clyde Martin Fearing, Art and the Creative Teacher, W.S. Benson and Company, 1971.

Select Awards

1961 Textile Award Arizona Crafts (Arizona Designer Craftsmen)

1961 2 American Designer Craftsman Award Arizona Crafts 61’

1961 Award of Merit Applied Art Center Arizona State College

1963 Tucson Art Center Merit Award Arizona Crafts 1963 annual exhibition

1964 1st Prize Arizona State Fair Craft Show

1965 Craft Guild Prize Craft Guild/Tucson Art Center

1966 Award Arizona State Fair

-

Nik Krevitsky Stitchery, c. 1970

Nik Krevitsky Stitchery, c. 1970Nik Krevitsky: On STITCHERY

Essay first published in the November/December 1963 issues of Craft Horizon magazine.

My stitcheries are appliqué and stitch panels—pictures, if you wish—which achieve graphic effects not possible through other means or materials. They depend upon the color mutations created through transparency, the textural potentials of networks of thread, and the use of a variety of fibers and weaves.

The design of my stitcheries is done with fabric, yarn, straw, raffia, leather, metallics, beads, feathers, and any other material which can be assembled by being stitched, or otherwise held or tied together with threads or yarn. Many fibers and threads which are used in weaving, and are too fragile for traditional needlework, are incorporated in ways which strengthen them. They are enclosed in veilings of net or sheer fabric ; they are held down with variations of couching ; or they are otherwise assembled to give durability to them and to the structure of the work.

Assembling these materials is a constant venture, and I doubt that I could work with the restriction of going shopping for the ingredients for a particular stitchery in advance of doing it. I find it easier to work with a wide selection at my immediate disposal. To do this, one must be constantly collecting stimulating materials and must have seemingly limitless storage space. I have purchased native materials whenever I have traveled, and this in itself has been an adventure.

The actual process of making a stitchery, for me, is : (1) selection of a base fabric, often linen ; (2) arranging fabric shapes on the base fabric ; (3) manipulating yarns and fibers in combination with these fabrics ; (4) starting to stitch, attaching fabrics to the base without concern for turning under the edges—or other needlework techniques of traditional appliqué or patchwork (the edges are held secure with the layer-upon-layer of stitches eventually used).

Sometimes stitching is done on a thirty-inch embroidery hoop before the base fabric is stretched and mounted on a frame. An assortment of needles is used, depending on the thread ; large curved upholstery needles are essential when working on a large panel. I often use hand- woven fabrics as a base, but, although I weave, I have not yet combined stitchery with weaving in progress. This is probably because I find it necessary to see the entire area of a panel when I am working on it. The constant change of relationships as each element is used affects what comes next and, of course, effects the end result.

Although one may find an extensive vocabulary of stitches in my work, I often use the simplest techniques. The straight or running stitch is most prevalent, and some pieces are done with it exclusively. When I build up heavy chained or looped lines or areas, these are held to the base by couching or being tacked down with a basting stitch. One of my favorite yarns for a strong raised surface is a heavy jute manufactured exclusively by Lily Mills, available in a subtle range of colors. This I use in contrast to the satin twists of cotton and silk embroidery yarns. Heavy hand-spun and hand-dyed yarns are often laid on the picture and held to it with fine stitches of embroidery floss in the same color.

I am intrigued with color and light and their interaction. The element of transparency is one which I use persistently, and its use is obvious in my work. I feel quite confident that this has been a direct effect of exposure to slides, films, and other projected imagery, such as television and X-ray.

Although I also paint, I do not translate my craft works from paintings or sketches. I develop them through continuous adjustments of the relationships of shape and color in the medium. Sketches and cartoons, whenever I use them, are samples in the material of the end product. I constantly hope this approach carries through to the completed work and that the work thereby retains a feeling of being “right” in terms of the material out of which it was created. The novel, when it is there, is something which has appeared naturally, out of an interaction between me and the material and whatever feelings, ideas, and experiences are brought to it.

I work on several pieces concurrently, finding decision making easier after a work has been seen over a period of time. Deliberation about areas, overlays, and changes goes on for some time. There is no such thing as right or wrong in the works; every stitch is part of the end product, even if it is covered over by several layers of fabric or net- works of thread. Sometimes the concept of close relationship pervades; at other times a feeling of tension or vibration is consistent with the concept. The works are no more alike than days are alike, nor are they more different than one person’s vision can make them.

-

-

-

-

-

-